![]()

ST ALEXIS OF UGINE (1867-1934)

TOWARDS

OVERCOMING THE DIVISIONS

OF THE RUSSIAN CHURCH IN WESTERN EUROPE

As is known, since 1926 the Russian Orthodox Church in

Europe has been divided into three separate 'jurisdictions'. These are:

Firstly, there is the worldwide Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia (ROCOR). This was given temporary independence in 1920 by the Patriarch of Moscow, St Tikhon (+1925), the head of the then persecuted Patriarchal Russian Church inside Russia.

Secondly, there is a group based in France known as the Paris Jurisdiction. This broke away from ROCOR in 1926 and later transferred its allegiance outside the Russian Church to the Greek Patriarchate of Constantinople.

Thirdly, a group which broke away from the second group in 1930. This placed itself directly under the Patriarchal Russian Church inside Russia, despite the ongoing persecutions there.

With the changes inside Russia, especially in the last twelve years, there have recently been further divisions and controversies within these three groups.

Having suffered problems in the late 1990's in Paris, the once small third group attached to the now freed Church inside Russia, then suffered difficulties in London from 2002 on. However, overall in the last five years, this group has expanded considerably in Western Europe with a flood of new immigrants from Russia. It now hopes to reunite all members of the Russian Church within a single Western Metropolia.

In 2001 there was a serious political division within the first group (ROCOR). This was centred in France and concerned attitudes to the possibility of an eventual reunion with the Church inside Russia.

Finally, in 2003, the fragile second group finds itself deeply and bitterly divided about a possible eventual reunion with the Russian Church and the place of Russians and native Western Europeans within itself. They have yet to answer a fundamental question: Does the voice of the True West coincide with the voice of Eternal Russia?

Whatever the Church authorities and episcopates decide and whatever happens to the Russian Church in Western Europe, there can be no doubt that future Church unity will be built not on politics, but on holiness. This is the one word and reality which many seem to have forgotten and overlooked; and yet it is the only thing that counts. Below, for the first time, we print in English the life of one who was linked with all three groups and who surely shows us all the way ahead - through holiness.

THE LIFE OF ST ALEXIS

He hath put down the mighty from their seats, and exalted them of low

degree.

Luke 1, 52

INTRODUCTION

Alexei Ivanovich Medvedkov was born on 1 July 1867 into the family of the young Fr John Medvedkov, in the village of Fomichevo near Viazma. The latter passed away soon after his son's birth and the little Alexis began a life full of privations and poverty and the usual path for a priest's son: church school and seminary, which he finished in 1889. Then came the problems of obtaining a post, giving him and his widowed mother some sort of security. Despite the views of his friends, the good conscience of the young man did not allow him to take up the difficult task of the priesthood at once, for he considered himself unworthy. First of all, he decided to test himself and prepare for the priesthood as a church reader and singer. With his fine bass voice, he obtained a position as choir-director in St Catherine's church on Vasilevsky Island in St Petersburg. Here he married.

THE PRIESTHOOD

After some five years spent here, Alexis went to the future St John of Kronstadt to whom he had sometimes confessed. Seeing this God-fearing man, Fr John blessed Alexis to serve as a parish priest. In December 1895 (old style) he was duly ordained deacon and two days later, priest, by Metropolitan Palladius of St Petersburg. The new priest was assigned to a poor parish in the village of Vruda in the Yamburg region of the province of St Petersburg, sixty miles from the city. Here Fr Alexis was to spend twenty-three years of his life.

Fr Alexis was loved by the 1500 peasant-parishioners in his church, built in 1840 and dedicated to the Dormition, and also by the children in the local schools and in the orphanage. His widowed mother Leonilla came to live with her son and baked prosphora for the parish. Two children, both daughters, were born to him. He would knock at every door, encouraging people to practise their faith; he would spend whole nights collecting materials for his sermons, he ordered books and read the Holy Fathers in his desire to feed his flock. And yet this was such a poor parish that the priest was himself obliged to work the land, plough and harvest, like his parishioners, in order to survive. Fr Alexis won the respect of his brother-priests. The church authorities recognised his zeal, humility and compassion, giving him several awards and in 1916 making him archpriest.

REVOLUTION AND EXILE

In 1917, then aged fifty, Fr Alexis was one of the first to be arrested by the Bolsheviks for his steadfast faith and then thrown into prison. Here he was tortured, his arms and legs broken, a nerve in his face torn and finally he was scourged and sentenced to death. However, extraordinarily, his eldest daughter gave herself up as a hostage and the ageing priest was released. The trace of these events remained on Fr Alexis' face for the rest of his life; he lost the use of a facial nerve and his right eye was always open wider than his left.

In 1919, however, the whole family managed to escape to Estonia where they lived at a place called Kochtla-Iarve. The life of a refugee and the lot of exile in Estonia were bitter. In order to feed his family Fr Alexis undertook hard physical work in a slate mine alongside Estonian criminals in their shackles. Now in his fifties, Fr Alexis found the work exhausting. He was given a surface job and finally that of night-watchman. In 1923 the Church authorities in Estonia attached him to a parish as an assistant priest. Serving the liturgy every Sunday, helping in the parish school and living in great poverty and exhaustion, in 1926 his matushka fell seriously ill. In 1929 came the next trial: matushka died, leaving Fr Alexis a widower.

UGINE

On the loss of his matushka, Fr Alexis petitioned Metropolitan Eulogius of the Constantinople Russian jurisdiction in Paris, asking to join his diocese in France. Finally, after many trials, in 1930 Fr Alexis arrived in France with his two daughters and a grandson. Here he was appointed rector of the St Nicholas Russian Orthodox church at Ugine near Grenoble in the French Alps. Here was a parish dependent on a local metallurgical factory set in the pine-clad mountains from which streamed the water to power its turbines. This factory employed some 600 Russian immigrant workers, mainly recruited in Estonia and the Balkans. The factory management had given the workers a large wooden workshop, which by 1927 they had turned into a church and had consecrated.

Although materially Fr Alexis' life was now better, he still looked like a typical Russian country priest, with an old, worn-out cassock and indeed, an old, worn-out face. However, he proved to be a man of prayer who paid great attention to the way in which the services were celebrated. He often celebrated on weekdays and the Sunday liturgy was very solemn, served with heartfelt faith. In this he was aided by the devotion of the choir which sang very well. Fr Alexis would arrive very early at church and pray for a long time. During the liturgy he intoned every word very clearly, made no omissions and often preached, his sermons being well-constructed and lengthy. After the service, Fr Alexis would stay on to pray, doing memorial services and other services for the parishioners, never taking money.

Although his material situation was much better, morally the Lord sent him new trials. His new flock, mainly composed of factory-workers, did not appreciate him, failing to understand his humility and truly Christian compassion. He would always strive to be on good terms with everyone and would not take sides in disputes. When insulted, he would reply with humble silence, he listened rather than spoke. If the conversation became political or was offensive to others. he would grow silent and begin to pray. With close friends, however, he showed his erudition and became talkative with regard to God and the Church. He frequently quoted the Gospels, and the Psalms, which he knew by heart, and also quoted the Church Fathers. He especially appreciated the Russian theologian, Khomyakov. He was well-read in literature and science too and he was particularly gifted with children whom he taught at the church school.

His parishioners remembered him as an honest, exceptionally modest man, rather delicate even shy, always thanking God, even in his great need. He was often engrossed in prayer, silent but also friendly, showing a prayerful humility and patient compassion, refusing to criticise. Since Fr Alexis used to give away much of what he received, his life in Ugine was still materially poor. Fr Alexis also found it difficult to adapt to the new conditions of politicised exiles. Unfortunately, his own children did not share his great faith. In the parish there were enemies. Some parishioners disliked his long services, others slandered him for his poor dress. Complaints were made to his Metropolitan in Paris. The parish council turned out to be particularly difficult, as it was dominated by secular-minded laypeople of a military background, used to giving orders. Their main interest was not the Church, but politics. Different cliques tried to drag Fr Alexis onto their side. Fr Alexis would not reply to them, remaining engrossed in silent prayer. He always defended the rules of the Church, on this making no concessions, and never taking part in politics.

Some parishioners actually began to harass Fr Alexis during the services. Finally, a group of parishioners denounced Fr Alexis to his Metropolitan who summoned him to Paris. Realising that the gentle and meek Fr Alexis was incapable of defending himself, another group of parishioners, almost four times more numerous, took his defence. Trembling with emotion, Fr Alexis went to Paris, where the Metropolitan also defended him. A new parish council was appointed, but Fr Alexis was not to remain in this world for much longer.

THE END AND THE BEGINNING

His health had been undermined not only by the tribulations of the Communists, but also by a horrible illness. Cancer of the intestine was diagnosed and Fr Alexis was confined to bed. In July 1934, Fr Alexis was taken to hospital in Annecy in Upper Savoy. Here, one of his most faithful parishioners came to see the lonely pastor and Fr Alexis confided in him. He told him how much he liked akathists and canons and then said the akathist to St Panteleimon, whom he particularly loved. He also said how much he liked children:

'In my parish the true parishioners are the children, the children of my parishioners…and if those children live and grow up, they will form the inner Church. And we too, we belong to that Church, as long as we live according to our conscience and fulfil the commandments…do you understand what I mean? In the visible Church there is an invisible Church, a secret Church. In it are found the humble who live by grace and walk in the will of God. They can be found in every parish and every jurisdiction. The emigration lives through them and by the grace of God'.

The last days of the earthly life of Fr Alexis were coming and he foreknew his death. Indeed, an operation brought no relief. In August 1934 more parishioners came to see him. He encouraged them all to live a Christian life, asking them to pray and fast. Fr Alexis suffered greatly; he knew that he was going to die. He never complained and his mind remained clear. Fearing sudden death, he called the nearest priest, belonging to the Church Outside Russia. Later his confessor came. In their absence he asked forgiveness of everyone, especially those who had once persecuted him, and blessed everyone. He prayed and wept, begging the grace of God. The day before he died, Fr Alexis received confession, unction and communion. His neighbours in the hospital ward related how on the eve of his death he sang church hymns and early in the morning humbly and peacefully went to the Lord. It was 22 August 1934.

After his death the doctors disclosed that Fr Alexis cancer was malignant, it had spread throughout his body. They demanded that he placed in a coffin immediately, for in the case of malignant cancer the body would decompose very rapidly.

All the Russians in Ugine, regardless of their jurisdiction, attended his funeral. This included those who had once denounced him. The funeral was marked by the cross, the banners, the Paschal vestments, the children holding flowers and dressed in white, the choir singing wonderfully, the coffin draped in white, the crowds of people. The solemn but joyful mood dissolved the sorrow of a dear loss. Everybody, even Fr Alexis' eldest daughter, weeping inconsolably, finished by calming down. Walking up to the hilltop cemetery, everybody felt that the soul of the dear, beloved pastor had departed not to the dark of the tomb but to the heavenly mansions of the Lord.

Fr Alexis was buried in the first available grave space, but then the new rector bought a concession for thirty years in another part of the cemetery with money he had collected from parishioners. This was to be the first transfer of Fr Alexis' body, during which the coffin lay on the surface for three days.

THE MIRACLES

After the Second World War the Russian Orthodox parish in Ugine transferred its jurisdictional allegiance from Constantinople to the Russian Patriarchal Church. In 1953 Ugine town council decided to build flats on the site of the old cemetery and open a new cemetery, where, in the coming years, families would be able to transfer the remains of their loved ones. Parishioners decided that it would be too expensive to pay for the reburial of Fr Alexis. However, the parish priest, Fr Philip Shportak, borrowed some money which he agreed to pay back in monthly instalments, and arranged to pay for the transfer out of his own pocket. On 22 August 1956, exactly twenty-two years to the day after Fr Alexis had passed away, council workmen came to Fr Alexis' grave.

For the last three years they had been working with shovels and pickaxes, collecting bones, placing them in small coffins and moving them to the new cemetery. Now they were at Fr Alexis' grave, expecting to pick up his bones too. Having dug down exactly four feet, the first wonder took place. 'An unknown force' (as they later related) impelled them to throw their tools away and begin digging with their hands. This turned out to be a miracle, for stupefied, they soon uncovered the body of the priest, who looked as though he had been buried only two or three days before.

He bore not the slightest mark; his face and hands looked as though they were made of wax. And yet the wood and metal of his coffin had totally disintegrated. Although the body had been in contact with the wet soil, yet both the body and the vestments with their white brocade and golden crosses, as well as the Book of Gospels on his chest, were intact. Only the metal binding of the Gospels had darkened with age. The workmen tested the material of the vestments, trying to tear it, but they could not. And yet here was the body, full of malignant cancer, which had died exactly twenty-two years before and which the doctors had said would decompose immediately.

The new coffin prepared for the removal of the remains was too small, for it was supposed to take only bones. Therefore the workmen had to cross the priest's arms over his chest and raise his knees. They discovered that the joints were very supple, like those of a living man. The whole body smelled fresh. The cemetery keeper, also a gravedigger, declared that in thirty years of career, during which he had frequently had to open graves, he had never seen anything like it. A doctor was called. He was amazed by what he saw and stated that the body of someone with a malignant cancer had never failed to decompose. 'It is a real miracle', he said. As they lifted the body from the grave, everybody thought that it would disintegrate. But this did not happen. The body remained quite intact.

For three whole days during the August heatwave, the small coffin containing the body lay on the surface. During that time it was opened on several occasions, since visitors, both Russians and French, came to see this phenomenon. Unbelievers thought that the body would start to decompose on contact with the air. But this did not happen. When the day came for the reburial in the new cemetery, it was raining. In fact it poured so hard that the workmen and others simply lowered the coffin into the new grave and then ran for cover, leaving the grave open and the faithful Fr Philip to do the funeral service in the driving rain.

Before the new grave was filled in, many came to look, especially Poles, Italians and French. Believers knelt and prayed. Unbelievers shrugged their shoulders in astonishment. At the request of Fr Philip, Metropolitan Nicholas of the Patriarchal Church came and celebrated a memorial service over the grave. Fr Paul Pukhalsky, a priest of the Paris Jurisdiction of Russians, came, spoke to eyewitnesses and then made a report to his Metropolitan, Vladimir. The priest suggested that the body be removed to the Russian cemetery church of the Dormition at Sainte-Genevieve-des-Bois near Paris. The Metropolitan enthusiastically agreed and a date for the transfer was fixed: 3 October 1957.

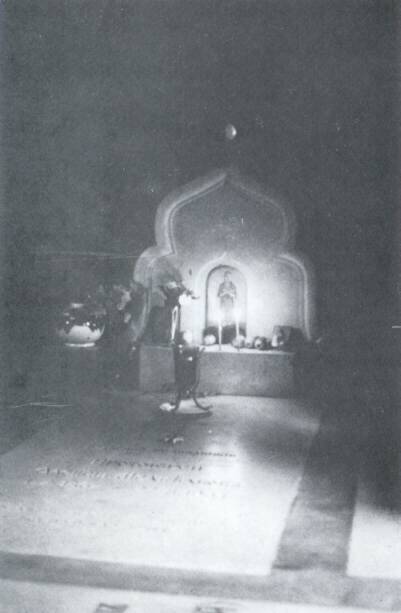

TO PARIS

On 30 September 1957, workmen preparing for this transfer, not openly opened the grave, but also, and without permission, once more opened the coffin. They and other eyewitnesses were startled to see that the body was still incorrupt, having suffered no change whatsoever. On the day of the transfer after a graveside memorial service, the coffin, inserted into a second zinc-lined coffin, was taken to the church in Ugine. Here another memorial service took place. Although it was a weekday, the factory had gone on strike, enabling a great many people to attend that service. The body arrived at Sainte-Genevieve-des-Bois, 500 miles away, in the evening of the same day, Thursday 3 October 1957. A man reported to one of the priests present that two people had already been miraculously cured of serious illnesses through the prayers of Fr Alexis. The relics were placed in the crypt of the church and a service was celebrated.

The next day, Bishop Methodius of the Paris Jurisdiction celebrated a liturgy in the church. This was followed by a memorial service at which representatives of the two other Russian Orthodox jurisdictions, ROCOR and the Patriarchal Church, concelebrated. Those disunited were thus united. In a sermon Fr Philip Shportak, said: 'Through the incorruptibility of His good shepherd, the Lord is calling all of us to remain faithful children of the Orthodox Church'. To this day the relics of Fr Alexis remain there and the faithful children of the Orthodox Church come to pray before them…

Holy and Righteous Father Alexis, pray to God for us sinners and unite us!

Priest Andrew Phillips

9/22 August 2003

69th

anniversary of the repose of Fr Alexis Medvedkov

47th anniversary of the uncovering of his incorrupt relics