THE LIFE OF ST NICHOLAS (MOGILEVSKY), METROPOLITAN OF ALMA ATA AND KAZAKHSTAN (1877-1955)

Commemorated 12/25 October and the first Sunday after 25 January (Feast of the New Martyrs and Confessors of Russia)

Vladyka Nicholas was an exceptional person. He had such a beautiful face - you can only call it a saint’s face. He was always smiling, he never refused anyone anything. And he always prayed for everyone (1).

He was born on Easter Sunday, 9 April 1877, to the family of a poor church choirmaster called Nikifor and his wife Maria. He was called Theodosius after the holy martyr Theodosius.

Vladyka used to remember: ‘Father was strict, he was very demanding in terms of order and tasks that we had to perform’. He was an expert in church singing. He was especially keen that everyone in church should sing and he passed on that love to his children. As for his mother, Vladyka Nicholas would remember: ‘Our mum was love itself. She never shouted at us, and if we did anything wrong, which of course did happen, then she’d look pitifully at us, and we felt terribly ashamed’. His grandmother Pelagia played a very important role in his upbringing. ‘On the long winter evenings’, he recalled: ‘Granny would take us up onto the stove and stories without end about God’s saints would begin’. Vladyka would also often reminisce about his grandfather, who was a priest too.

In 1904 Theodosius’ long-held dream came true. On the eve of the feast of St Nicholas the Wonderworker, at the Hermitage of St Nilus of Stolbensk, Theodosius became a full monk, with the name of Nicholas. In May 1905 monk Nicholas was ordained hierodeacon and on 9 October 1905 hieromonk. At the insistence of the monastic brethren, in 1907 Fr Nicholas entered the Moscow Theological Academy, from which he successfully graduated four years later.

In Chernigov in October 1919 Archimandrite Nicholas was consecrated Bishop of Starodub, Vicar of the Chernigov Diocese. From that time on Bishop Nicholas’ ministry was placed under the grace-filled protection of St Theodosius of Chernigov, whom Vladyka greatly venerated.

In 1923 Bishop Nicholas was appointed Bishop of Kashir, Vicar of the Diocese of Tula, where the situation at that time was very difficult. Modernist renovationists had taken control of the vast majority of the parishes. But with his little flock Bishop Nicholas fought against the enemies of Orthodoxy. The result of this struggle was Vladyka’s arrest, on 8 May 1925.

Vladyka spent over two years in prison. After his release, he was appointed Bishop of Orel. He served there until his next arrest. This is what Vladyka said of that time: ‘On 27 July 1932 I was arrested and sent to Voronezh, where a criminal investigation took place. It is not fitting to speak of the conditions in which I lived then, because the whole country was suffering at the time.

When the investigation was over, the investigator and myself parted with regret. He said to me in confidence: ‘I’m glad my investigation has managed to be of at least some use to you, in that I’ve succeeded in proving your evidence correct. This is important for you, now you’ll be sentenced under a different article of the law and you won’t get more than five years, instead of ten’. ‘What will I get five years for?’ I blurted out involuntarily. ‘For your popularity. People like you have to be isolated for a time, so people will forget your existence. You have too much authority with the people and your sermons are very important for them. They follow you!’ ‘I hadn’t expected to hear this assessment of my ministry from the mouth of a representative of that institution, but such was the case. O Lord, glory to Thee! Glory toThee, O Lord! A sinner, I served Thee as I could! I could only repeat those words from the joy that filled my heart. Now no sentence could frighten me’.

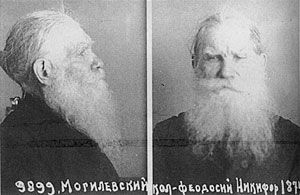

Photographs from the prison file of Bishop Nicholas (Mogilevsky)

Recalling his wanderings through the camps, Vladyka talked a great deal about Sarov, where he spent quite a long time. ‘After the monastery had been closed and looted, they set up a corrective labour camp and that was where I went. When I crossed the threshold of the holy monastery, my heart was filled with such inexpressible joy that it was difficult to contain myself. ‘Look’, I thought, ‘the Lord’s brought me to Sarov Monastery, to St Seraphim, who I’d repeatedly turned to in fervent prayer in the course of my life’.

Again and again I’d kiss all the monastery grills and windows. At that time St Seraphim’s cell was still intact. The whole time I was in Sarov, I considered I was fulfilling an obedience to St Seraphim, through whose prayers the Lord had sent us consolation such as we only have at the end of the Liturgy, when we commune with Christ’s Holy Mysteries.

In 1941 Vladyka Nicholas was made Archbishop.

Vlayka heard the news of the outbreak of the Great Fatherland War, just as he was about to celebrate the Divine Liturgy.

‘I was doing the Proskomidia’, recalled Vladyka, ‘when one of my friends told me the dreadful news in the calm of the sanctuary. What could I say to the tearful flock, who were awaiting not consolation from me, but from Christ? I could only repeat what St Alexander Nevsky had said before: ‘God is not in force, but in truth.

That year the 22 June (the date of the German invasion) fell on the Feast of All the Saints who have shone forth in the Russian Land. I think that has a special significance. We endured such a difficult trial because of our sins, but the saints of the Russian land had not forsaken us. We turned to them, our compatriots, for prayer and help. And heavenly aid was revealed when it was least expected’.

After this news, a new trial began for Archbishop Nicholas. On 27 June 1941 Vladyka was arrested and imprisoned in Saratov. Here he spent six months altogether. Then he was sent to the town of Aktiubinsk in Kazakhstan and three months after that to Chelkar, a town in the province of Aktiubinsk.

When, many years later, Vladyka was asked how he had reacted to the deportation and if he had had a feeling of insult and protest in his heart, he answered: ‘Everything is God’s Will. It means I needed to go through that difficult trial, which finished with great spiritual joy’.

‘Just think how it would be for someone’s near and dear, if he were to spend his life in comfort and ease. A life abounding in material goods leads to the stony hardening of the heart, to a cooling of the love of God and your neighbour. From excess, people grow cruel and fail to understand the misfortunes and sorrows of others’.

Vladyka went into voluntary exile in a prison train. The train pulled into Chelkar station at night. The guards pushed Vladyka out onto the platform in his underwear and a torn quilted jacket. All he had on him was a certificate, which he had to produce twice a month when he was to report to the NKVD (Secret Police).

Vladyka sat out the rest of the night at the station. Morning came. He had to go somewhere. But how could he go anywhere in the winter in such a state? In any case he had nowhere to go. Vladyka was forced to ask some old women for help and in their kind-heartedness they did not refuse him. One old woman gave him a padded jacket, another a fur hat, another patched up felt boots. Another let him stay in a barn where she had a cow and a pig. Vladyka was nearly 65 at the time. His hair was white and when you saw him you could not help feeling sorry for him. Vladyka tried to get work, but nobody would take him on – he looked older than he was. He was forced to ask for alms, so as not to starve.

Later, when his spiritual children asked Vladyka why he did not tell the old women who had given him clothes that he was an archbishop, he answered: ‘If the Lord sends you a cross, He gives you the strength to carry it, He lightens it for you. In such cases your own will mustn’t show itself, you must give yourself up completely to the will of God. To go against God’s will is unworthy of a Christian and after someone has patiently suffered the trials sent to him, the Lord sends spiritual joy’, Vladyka finished explaining.

And so, until the end of autumn 1942, Vladyka continued to drag out his existence as a beggar. His physical strength was all but exhausted. From lack of food and the cold he was emaciated, his body was covered with abcesses, he had lice from the filth. He was losing strength, not by the day but by the hour...

And so came the moment when his last strength left him and Vladyka lost consciousness.

He came to in hospital, in a clean room and a clean bed. It was bright and warm, people were bending over Vladyka. He closed his eyes, deciding that none of this was true. One of those bending over him felt his pulse and said: ‘Well, well, almost normal! Our grandad’s come to!’ Vladyka was slowly recovering. And when he got out of bed, he at once started to try and help those around him. He would give one patient some water, another the bedpan, another needed tucking in, another would need a word of comfort. They came to love the old man in the hospital. They all started to show him affection and call him ‘grandad’. But only one young doctor knew the tragedy of this ‘grandad’, only he knew that once he had been let out of hospital, he would once more have to go and beg and live next to a cow and a pig.

And so came the day when it was suggested that ‘grandad’ would have to leave hospital. Vladyka Nicholas began to pray to the Lord, giving himself up to His will: ‘O Lord, I’ll go wherever Thou sendest me!’ And when everyone gathered to make their farewells to the kind-hearted ‘grandad’, a nurse came in and said: ‘Grandad, they’ve come for you!’ ‘Who had come?’ they all asked together. ‘Why, that same Tartar who brought you parcels sometimes, surely you remember? Of course, Vladyka could not remember how often, every ten days, some unknown Tartar would send him some Tartar cakes, a few eggs and some sugar. And Vladyka was yet to discover that it was that selfsame Tartar who had picked him up, half-dead, as he was lying unconscious in the street and brought him to hospital. Amazed, Vladyka went to the hospital exit. And there indeed, in the doorway, stood a Tartar holding a horsewhip. ‘Well, better now, grandad!’ he said to Vladyka and smiled kindly. Vladyka also greeted him. They went outside, the Tartar sat Vladyka in his sled, sat down and off they went. It was the end of winter 1943. ‘What made you decide to take an interest in my life and be so kind to me? You don’t even know me,’ asked Vladyka. ‘We have to help each other’ answered the Tartar. ‘God said I must help you and save your life’. ‘Who said God to you?’ asked Vladyka in astonishment. ‘I don’t know how’, replied the Tartar, ‘when I was going about my life, God said to me: ‘Take the old man, you must save him’.

A quiet phase began in Vladyka’s life. The Tartar had contacts and was able to arrange things, so that Vladyka’s spiritual daughter, Vera Athanasievna Fomushkina, soon came to Chelkar. She had also been exiled, but to a different area. Vera did not try to conceal from others the identity of the ‘grandad’, whom people in Chelkar carefully nursed back to health.

On 10 October 1944, Vladyka himself sent a letter to the People’s Commissar for Internal Affairs of the USSR with ‘the diligent request’ that his status of ‘voluntary exile’ be lifted and that he be allowed to go to Russia and take up an episcopal position, as directed by the Synod of the Patriarchate. On 19 May 1945, by decision of the Special Committee of the People’s Commissariate of Internal Affairs of the USSR, Vladyka Nicholas was released early. On 5 July 1945, by decision of the Holy Synod, the Diocese of Alma Ata and Kazakhstan was formed and Archbishop Nicholas (Mogilevsky) was appointed as Diocesan.

St Nicholas celebrating in church

Vladyka arrived in Alma Ata on 26 October 1945, the feast of the Iviron Icon of the Mother of God.

Vladyka was unusually zealous as regards the services, which he celebrated as closely as possibly to the monastic standard. He always served with reverence and never hurried. If, when Vladyka was serving, the choir began to rush, he would look out of the sanctuary and ask: ‘Who’s in a hurry to catch a train?’ Everyone was ashamed and the choir immediately began to slow down.

From the reminiscences of Valentina Pavlovna Khitailova in Yelets:

Vladyka himself often stood with us on the choir. He loved to sing the early liturgy on the left choir. He would himself give the tone. He had a velvety baritone, it was very soft and beautiful. When Vladyka sang, his soul entered into the singing. Especially in the Great Fast, he would come out into the middle of the church and sing, ‘O my Saviour, I see Thy Bridal Chamber adorned’. He sang from the soul, with yearning. His voice poured out into the church, there was total silence, all that could be heard were the bells on the censer and people weeping.

Vladyka himself always cried. His tears were particularly noticeable on his velvet Lenten vestments, when the lights were turned on at the evening services. They were like threads of pearls. And what was remarkable is that when we cried, we could neither sing nor read, but when Vladyka cried, he could at the same time intone his parts of the service in a clear voice.

Vladyka also prayed at home with great zeal and tears, dressed not in his bishop’s vestments, but in those of a monk. Every morning and every evening Mother Vera would hang dry towels by his lectern and collect them wet, soaked with Vladyka’s tears.

A zealous man of prayer, Vladyka especially loved and venerated the Mother of God. For the great spiritual consolation of his flock and for the first time in Alma Ata, Vladyka began to celebrate the marvellous service of the Burial Shroud at the Feast of the Dormition of the Most Holy Mother of God. Whenever anyone was in difficulty or ill, Vladyka advised them to make as exacting a confession as possible, take communion and only then take action to correct the situation in which he found himself, for example by taking medicine. ‘An impure confession is the root of all misfortunes. Why? Because the Lord wants everyone to be saved and so He saves us through all sorts of misfortunes. Only in misfortunes do we remember God, for when everything goes well for us, we forget Him.

At Easter and Christmas Vladyka’s doors were open to everyone. Everyone greeted each other with a kiss, glorifying God! Everyone! Everyone! Everyone! ‘At Easter’, as the choir members recalled, ‘after the service in the church we went to Vladyka’s rooms and congratulated him. We would sing through the whole Easter service, but that was not enough for him and he would ask: ‘Let’s sing again...you know, it’s such a joy we have here!’ On the Great Feasts Vladyka was as happy as a little child.

At Christmas people came to him to glorify Christ. He started to give us presents. And we were happy that Vladyka was so benevolent, radiant like the sun to us. Light seemed to come out of every wrinkle on his face.

As a true monk, Metropolitan Nicholas lived very modestly. According to Alexandra Andreyevna Zubtsova: ‘He had a table, a hard bed (he slept on planks) and benches. There was a room set aside for prayer, where there were some icons, a bookshelf and a desk’.

Vladyka’s childlike simplicity, guilelessness, prayerfulness, faithfulness to his monastic vows, finally, the very sight of the elder, disposed people’s hearts to him. ‘In his white cassock, with the snow-white locks of his hair and fairy-tale beard, in the garden surrounded by flowers, benevolent, smiling, Vladyka seemed to have come from a completely different age, where there were no trams, aeroplanes, studies of the stratosphere...’. That is how people who knew Vladyka described him.

Archbishop Nicholas of Alma Ata often said: ‘My friends, do not forget me a sinner in your prayers now and after death. I do not forget you and never will. If I am granted boldness, if only the Lord will take me into His abodes, if He forgives me and has mercy on me, then I will pray for you even after my passing into the other life’.

After every Liturgy, Vladyka would stand at the front, blessing everyone, despite the fact that on Sundays and feastdays there were up to a thousand or more people in church.

‘Vladyka’, his spiritual children would say to him, ‘you know it’s difficult for you to stand and bless people for such a long time after the service. You should give a general blessing and go home to rest’. ‘Oh, oh, you don’t realize how much our Orthodox people love and value a bishop’s blessing’, answered Vladyka and, falling silent, continued: ‘Yes, sometimes I’m so tired that I think: ‘I’ll give a general blessing’. But after that, I think: ‘Suppose, the Lord suddenly calls me to Him today and asks how I left my flock?’ That thought gives me extra strength and I bless the people’.

He loved everyone with the same, divine love and he expended that love on everyone he met.

From the reminiscences of Maria Alekseyevna Petrenko in Alma Ata:

‘It was 1948. My life, like that of millions of others in the difficult post-war period was very hard. My husband, father and brother had been killed in the war. I had two children left. On top of that, I had developed a serious infection in my left lung.

I cried a lot and got so depressed that I began to think of suicide. I thought, I’ll end it all and then it’ll be easier for me. I’d never seriously thought about the real meaning of religion. And then once in a dream I heard someone saying to me: ‘Go to Vladyka, he’s good. He’ll help you. And you must baptize the children’…Now I no longer remember, whether that was in a dream or in reality. Probably my soul was asking for help and perhaps my Guardian Angel was urging me on, go, seek and you will find!

I found out who Vladyka was and where he lived. After work at 6 o’ clock one evening I went to the wicker gate of No 45 Kavalerisky Street. An elderly woman opened the door and asked why I’d come. I said I wanted to tell Vladyka about myself.

When I saw Vladyka, I began to shake, I felt as if I couldn’t say a word. ‘Hello’, I just managed to get out. ‘Calm down, my child’, said Vladyka affectionately. He stroked my hair, sat me on a chair and asked the woman to give me some water. As I began to drink the water, my teeth chattered on the edge of the glass. ‘Please, calm down, there’s no need to cry, you should have come here long ago’, I heard the elder’s affectionate voice say again.

When I’d calmed down a little, I began to speak...I told him about my life, my illness and the terrible thing I’d thought of doing. ‘So, glory to God!’ he said. ‘It’s good that you’ve simply come to me!’ After I’d spoken to him, Vladyka explained what a great sin suicide is. ‘However hard it is, you mustn’t of your own will interrupt your life, you needed to turn to the Lord in prayer, He’ll always lighten the cross given to you’. Then he stood up and praised God: ‘Glory to thee, O Lord, glory to Thee for everything at all times!’ I stayed with Vladyka until ten in the evening. It was hard for me to believe that all this was happening to me. And I’d become so happy and felt so light! Yes, really, I felt that God was with us!’

An interesting and extremely edifying event took place in July 1947, when Vladyka Nicholas had to fly to a meeting of the Holy Synod in Moscow.

On boarding the plane, Vladyka stood with his companions at the entrance and blessed all the passengers as they got in. Vladyka always went everywhere in his cassock, despite the fact that people often mocked him as a result.

And on that occasion too the passengers, seeing that a clergyman was blessing them, began to make fun of him and stinging comments could be heard: ‘Well, we won’t be afraid of flying, we’ve got a saint with us!’ Scarcely one passenger had a good word to say. ‘But I didn’t listen to them’, said Vladyka when he returned. ‘I felt sorry for them. You know people don’t even suspect that the blasphemy they speak doesn’t come from their own minds and understanding, but they’re carrying out the evil will of the enemy of mankind. I blessed them all calmly’.

Everyone sat down...the plane took off. After a while the pilots suddenly began to grow concerned. Finally, the senior pilot made an announcement. There was danger – an engine had shut down. The situation was threatening, a disaster was looming. Panic spread among the passengers. But Vladyka said: ‘Let’s pray! Not a single soul will perish!’ Then he added: ‘Only we’ll get a bit dirty in the mud’. Vladyka got up and started to pray. The passenegers got more and more panicky. Nobody paid any attention to Vladyka, but after a few minutes everyone started to quieten down, they got out of their seats and listened to him praying. He was praying, asking the Lord to save everyone in the plane. At that moment the plane began to descend. But to the amazement of the pilots, who knew what that descent meant, the plane did not crash, as would be normal, but glided and gently landed. The plane had landed in a shallow, marshy lake. When people had calmed down a bit after the fear they had experienced, they began to go up to Vladyka and thank him. The senior pilot also went up to him: ‘This is a miracle, father’, he said, ‘forgive us for making fun of you!’ ‘God will forgive you’, replied Vladyka. ‘Thank God and His Most Pure Mother and put your hope in St Nicholas’.

From the reminiscences of Archpriest Valery Zakharov, the Rector of St Nicholas Cathedral in Alma Ata:

In the 1970s Metropolitan Joseph (Chernov) of Alma Ata and Kazakhstan said these words in one of his sermons: ‘We in Alma Ata live at the foot of the Tian-Shan mountains. On the one hand, we have the joy of seeing the beautiful sight of these mountains, but on the other hand the mountains conceal the danger of earthquakes and flooding. But Alma Ata will not be washed away by floods and will never be destroyed by an earthquake, because we have such remarkable men of prayer as Metropolitan Nicholas and Schema-Archimandrite Sebastian’ (2). Vladyka Joseph said that and I remember his exact words.

A visit to the town of Uralsk remains very clear in the memory of the senior subdeacon Ariy Ivanovich Batayev. ‘It was a summer at the beginning of the 50s. Vladyka was celebrating in the Cathedral of the Holy Archangel Michael in Uralsk. After the service he began talking to the parishioners. People were complaining to Vladyka about the heat and the drought in the Uralsk province. Since the snow had melted, there hadn’t been a single drop of rain.

Vladyka said: ‘Let’s pray to the Heavenly King, perhaps He’ll hear our prayer’. They began to do the service of intercession for rain. And there was a miracle. The sky, where there hadn’t been a single cloud, darkened and covered with heavy thunder clouds and it began to rain, not ordinary rain, but it poured with hail, it bucketed down. The walls of the old Uralsk Cathedral trembled from the peals of thunder. Vladyka paused in the service and said: ‘Orthodox people, isn’t this a miracle!’

When the service was over, everyone waited until the hail had more or less stopped and then went outside. They breathed the clean, fresh air. Vladyka had to walk about 200 yards to the rector’s house, but after the hail, the path had turned into a mudbath. Filled with love and gratitude to Vladyka, people there and then took off clothes and laid them down for him to walk on.

Vladyka’s prayerful mood did not leave him during his final illness. On Sunday 23 October 1955, after his last communion of Christ’s Holy Mysteries, when the nuns in the dining room were about to sing, ‘The Counsel from before eternity...’, Vladyka, straining his voice, called out to them from the bedroom: ‘Mothers, mothers, let’s stop there. Now let’s start the funeral service for a bishop’. They stopped singing, but they could not hold back their tears. Vladyka prayed especially loudly and intensely on the night of 23-24 October. They heard the words: ‘O Lord, do not judge me according to my deeds, but act with me according to Thy mercy!’ He repeated many times and with great feeling: ‘O Lord! Grant me mercy and not judgement!’

On Monday 24 October, the eve of his repose, Vladyka spoke a little once more. He said something particularly affectionate to everyone, as if saying goodbye. At about 5 o’ clock in the evening, his heartbeat became painful, and after that he said nothing more and lay with his eyes closed. On Tuesday morning he found enough strength within him to cross himself several times, as the akathist to the Great Martyr St Barbara was read at his bedside

After four o’clock on the afternoon of 25 October, those around him noticed that the end was approaching. They began to read the service for the departure of the soul, put a lighted candle into his hands and, as the last words of the canon were read, the bishop quietly and calmly breathed his last. It was at 4.45, just as they were ringing for Vespers in the Cathedral on the eve of the Feast of the Iviron Icon of the Mother of God, at which Vladyka himself so loved to exclaim: ‘Rejoice, Good Doorkeeper, who openest the gates of paradise to the faithful!’

On 28 October 1955 Bishop Hermogen (Golubev) of Tashkent and Central Asia, together with a host of clergy, performed the funeral service for Vladyka Nicholas in the Cathedral in Alma Ata. They carried the coffin with the precious remains all the way from the Cathedral to the cemetery - a distance of over four miles. According to police estimates, some 40,00 people followed behind the coffin. The cemetery was filled to overflowing with people, so that the clergy in the procession behind the coffin had difficulty reaching the grave. They served a litia at the graveside and Bishop Hermogen gave up the body of the reposed hierarch to the earth.

When it was all over and the grave mound piled up and covered with wreaths, in the moonlit silence of the gathering dusk, all present sang the troparion to the Good Doorkeeper, who opens the gates of paradise to the faithful.

In the Year 2000, at the Council of Bishops of the Russian Orthodox Church, the confessor for the Faith of Christ, wonderworker and intercessor for the Russian land and Kazakhstan, Metropolitan Nicholas of Alma Ata and Kazakhstan, was glorified as a saint.

Note:

1. From the reminiscences of Alexandra Andreyevna Zubtsova. This life of St Nicholas was prepared from the remarkable book by Vera Koroleva, St Nicholas, Metropolitan of Alma Ata and Kazakhstan. All the reminiscences of the Saint’s spiritual children are taken from there. The basic information for the above is taken from the article of the same name, placed on the website of St Nicholas Cathedral: http://www.nikolay.orthodoxy.ru/saints/nikolay/

2. For St Sebastian of Karaganda, a full life is now available in English. See: Elder Sebastian by Tatiana V. Torstensen, Platina 1999 (Translator’s note).

Translation: Fr Andrew Phillips