HOME PAGE HOME PAGE

|

|

The

Flag of England

By

EADMUND

I

have always considered our Union Flag to look gaudy and crude alongside,

say, the dignified and impressive flags of Imperial Germany or Austro-Hungary.

I also believe it to be heraldically incorrect. That is why the so-called

'Union Jack' has never excited any patriotic fervour in me. I have always

found the simple crosses of the individual saints of England, Scotland

and Ireland to be more æsthetically satisfactory, unsullied by a

superimposition that must always remind us of the Norman conquerors, whose

arrogance and ambition forced us into an unnatural marriage. As an Englishman,

the red cross of St George on a white ground always appeared to me to

be a far better design artistically, although it is rather plain, and

seemed lacking in some undefined particular.

The

great problem with the cross of St George is that St George is not England's

original patron-saint. St Edmund (Eadmund), King of East Anglia, has held

that distinction since the 9th century, when he gave his life in defence

of his faith and his homeland against the Vikings. Like St George the

Great-Martyr, he was martyred in a particularly horrible manner, and his

supreme self-sacrifice impressed the Righteous King Alfred the Great,

strengthening the latter's resolve to hold Christian Wessex against all

the odds.

St

Edmund continued to be revered as the patron-saint of England long after

the Norman Invasion. For example, the late fourteenth-century Wilton Diptych

in the National Gallery shows him in a place of honour. However, when

the Crusades really got under way (the first trial run against England

in 1066 having been successful), the Norman oppressors of this country

then went off to exotic lands to continue their unhappy holocaust of rape

and pillage. This culminated in the sack of Constantinople in April 1204,

when the Cathedral of Hagia Sophia (Holy Wisdom) was desecrated and a

prostitute was seated on the Patriarch's throne: an insult that Greek

Orthodox especially find hard to forgive and will never forget.

During

their sojourn in foreign climes, the Norman freebooters and their companions

encountered St George, and when they returned home, they developed his

cultus in this country. But the saint they venerated was not the

Great-Martyr known to Old England. Instead they turned him into a mediæval

knight in armour, battling against a dragon‡. In 1348 a small group

of Norman soldiery, together with the contemporary representative of the

depraved Plantagenet line, Edward III, formed the Order of the Garter:

a small, privileged clique with the pseudo-St George as its patron.

It

is possible that this patronage was adopted in order to mask the less

pleasant attributes of the order, as some have seen in its ritual and

numerology a pagan, and even Satanic influence*. St Edmund's relics had

been stolen by the French in July 1217†, and without their presence

in this country his influence faded. It was not long before the Norman

military as a whole adopted the distorted version of St George, and from

there he became accepted, by a people long deprived of their true heritage,

as the patron of England.

Much

later on, when the worst excesses of the Norman jackboot had been thrown

off, the Barons had self-destructed in the Wars of the Roses and their

remains had been crushed by the Machiavellian Tudors, a great Englishman,

William Blake, conceived some inspired and inspiring words. He wrote the

words of what some consider to be the true English National Anthem:

And

did those feet in ancient time

Walk upon England's mountains green?

And was the holy Lamb of God

On England's pleasant pastures seen?

And did the countenance divine

Shine forth upon our clouded hills?

And was Jerusalem builded here

Among those dark satanic mills?

Bring

me my bow of burning gold!

Bring me my arrows of desire!

Bring me my spear! O clouds, unfold!

Bring me my chariot of fire!

I will not cease from mental fight,

Nor shall my sword sleep in my hand.

Till we have built Jerusalem

In England's green and pleasant land.

These

words burned themselves into my head in childhood, and have lasted with

me throughout my adult life. Although the bow of burning gold has been

elusive, I have endeavoured in a small way to carry on the fight.

Incensed

by the unpatriotic celebrations of the 900th anniversary of the Battle

of Hastings in 1966, in that year I raised a petition in Tenterden in

Kent and presented it to Hastings Town Hall. One of the results of this

was my founding of þa Engliscan Gesiþas (The English Companions),

whose aim is to foster an interest in, and understanding of, all things

English. It was no accident that the emblem of our true Patron Saint became

the badge of the Fellowship - a gold crown and arrows on a red ground,

surrounded with a blue circle. The background colours were chosen from

Old English cloisonné enamel work and garnet jewellery.

The

Old English did not have flags. The nearest they came to a flag, in the

sense that we understand it, was a kind of elongated pennant in the shape

of a dragon. They also had other standards, and there are various examples

of this, such as the standard that was carried in front of King Edwin

of Northumbria, in imitation of the Roman Emperors. So, apart from a one-off

pennant consisting of a gold crown-and-arrows appliquéd onto a

ground divided diagonally into red and blue, which I made to fly beside

my tent when I visited the excavations of the Old English 'city' at Mucking

in Essex, the question of a flag did not really arise.

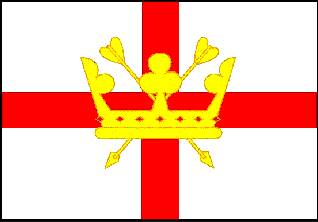

Then Father Andrew sent me an email, asking me what I thought should be

the national flag of England. He too felt that St George's Cross, now

sadly deformed into the standard of the national football team, was not

enough. I replied that I had not considered the matter, but that the crown-and-arrows

should come into it somewhere. He then suggested something like the East

Anglian flag, devised in 1902. This consisted of three gold crowns on

a royal blue shield, imposed on the centre of a red cross. I rejected

that idea, however, as being too provincial. I felt that many would resent

the aggrandisement of East Anglia over, say, Wessex or Kent. Then Father

Andrew told me that the red cross on a white ground was also the flag

of Jerusalem, and mentioned William Blake. In a moment of inspiration,

I superimposed the crown-and-arrows, with seven jewels in the crown, to

correspond to the traditional seven kingdoms of the Old English, on the

cross of St George. The feeling of 'something missing' disappeared, and

the flag, whole and complete, was before me.

Of

course also it has the great advantage that tradition is fulfilled. For

all that St George's likeness has been twisted, and folk have attributed

to him the honours due to St Edmund, he has acted as our patron-saint

for many years, and has fulfilled his charge well. Devotees of St George

can feel that the basis of the English flag has not been changed - it

has simply been added to, complemented, made complete. If you feel that

England should have her ancient heritage restored to her, then please

show your solidarity by flying this flag, and using the image of it wherever

possible. As a start, I plan to make available stickers bearing the design,

which can be put on correspondence as well as other uses. Details of the

price and contact address will be released shortly on this site.

‡

It was probably this mythical element, at least in part, which caused

the Pope to 'demote' St George in 1969.

*

See Pennethorne Hughes: Witchcraft: Penguin Books 1965, p. 109.

†

See Bryan Houghton: Saint Edmund - King and Martyr: Terence Dalton

1970, p. 54. The relics were returned to England on July 25, 1901, when

they were placed in the private chapel of the Duke of Norfolk in Arundel

Castle, Sussex, awaiting the completion of Westminster Roman Catholic

Cathedral. The authenticity of the relics was then questioned, however,

and they still lie in Arundel. Op cit, p. 78 et seq.

|

|

|

|