![]()

Behind the Sourozh Phenomenon:

Spiritual Freedom or Cultural Captivity?

Meletios Metaksakis, Metropolitan, Archbishop, Pope and Patriarch

The recent deeply tragic events in the Sourozh Diocese of the Moscow

Patriarchate have pleased no-one, splitting small parishes and even families

into two. Many believe that these events are closely connected with the

reconciliation of the now free Patriarchal Church with the Russian Orthodox

Church Outside Russia (ROCOR).

The fact that the two parts of the Russian Church now see eye to eye on most essentials means that the minority modernism of the old Sourozh is now sidelined. Modernism does not reflect the spiritual freedom of Orthodoxy, but merely the cultural captivity of an ideology dependent on Western cultural prejudices. The old modernism simply does not fit in with the Patriarchate’s hopes for a new and united Russian Metropolia of Western Europe, the foundation of a future Local Church in Western Europe. Today, only under Constantinople does modernism stand a chance of survival. Hence the schism.

These tragic events have therefore once again focused attention on the extraordinary universalist and meddling pretensions of the Patriarchate of Constantinople. Where did these strange and novel ideas originate? When and why did the Patriarchate of Constantinople first claim a type of universal authority, deliberately misinterpreting Canon 28 of the Council of Chalcedon? When did it adopt its so divisive ecumenist and modernist stance, which is now once more splitting the Orthodox Church in the British Isles and Western Europe?

The answer to these questions can be found below, in this interesting article, researched and written by a Serbian priest, Fr Srboliub Miletich. It explains the origins of the above phenomena, of particular interest to English readers since the now forgotten British imperialist politicking of the time lay behind many of them. We are indebted to Fr Srboliub for this very thorough article, which answers so many of the question which Orthodox are asking themselves today.

Though in the world and with the firm hope of saving all that is best in the cultures in which God has called us to live, we are not of the world. For this reason we do not take on the spirit of this world, worldliness. We must remain spiritually free, not cultural captive. At times, this means being critical of the defects in the culture into which we were born, without falling into some slavish and uncritical admiration of other cultures. This is what the Pahhellenist politician, Meletios Metaksakis, following the fashions of this world, did not understand. It is also what 'modernist Orthodox', who do not wish to conduct missionary work among the tens of thousands of Slavs recently arrived in this country, do not understand. May God help us all to live according to His commandments.

Fr Andrew

Meletios Metaksakis

July 1935. Zurich, Switzerland. After six difficult days in the throes of death, there dies a man whose personality was one of the most scandalous in the two-thousand year history of the Orthodox Church. His body is taken to Cairo in Egypt and buried with great pomp. One of the greatest Church reformers leaves behind him a painful, unstable and alarming situation, the consequences of which will be felt for many decades, probably even centuries. Against the background of his image and actions, a question arises. What was his personal contribution to contemporary and future tribulations, concerns and challenges facing the Orthodox Church?

We are now at a sufficient historical distance for both historians and theologians to give an objective assessment. Today, in our view, his personality and contribution demand this. We shall attempt to show why. We present only the basic information and some of the historical facts, which concern this personality, unprecedented in Church history. In his relatively short, but very tempestuous life, this man managed to become the head of three autocephalous Local Churches and to have taken a number of decisions, which until his time were incompatible with Orthodoxy. Here was a man who tried to change the very bases of Orthodox ecclesiology, raising questions to which many generations of Orthodox theologians are still to give mature and spiritually sober answers. But let us start at the beginning.

Patriarch Meletios Metaksakis was born on 21 September 1871 in the village of Parsas on Crete and was baptized Emmanuel. In 1889 he entered the Holy Cross seminary in Jerusalem. In 1892 he became a monk and was ordained hierodeacon. After completing his theological education, in 1900 Patriarch Damian appointed him secretary of the Holy Synod of the Patriarchate of Jerusalem. Eight years later, in 1908, the same Patriarch expelled Meletios from the Holy Land for 'activities against the Holy Sepulchre'. (1)

According to the historian Alexander Zervoudakis, an official in the British Ministry of Defence (1944-1950), in 1909 Meletios visited Cyprus and there, together with other Orthodox clergy (2), became a member of a British masonic lodge (3). In the following year Metaksakis became the Metropolitan of Kition in Cyprus and already in 1912 tried to become the Patriarch of Constantinople. Failing in this, he devoted himself to becoming the Archbishop of Cyprus. Meanwhile his undisguised political ambitions, authoritarian character and, above all, his modernism seemed to have played a decisive role in his defeat (4). Disillusioned, he left his flock and in 1916 headed for Greece. There, in 1918, with the support of his relative Venizelos, who headed the Greek government, he became the Archbishop of Athens. In the following year, when Venizelos lost the Greek elections, Metaksakis was deposed.

While still Archbishop of Athens, Metaksakis visited Great Britain together with a group of his supporters. Here he conducted talks on unity between the Anglican Church and the Orthodox Churches. At that time he also set up the famous 'Greek Archdiocese of North America'. Until then there had been no separate jurisdictions in America, but only parishes consisting of ethnic groups, including Greeks, and officially under the jurisdiction of the Russian bishop. With the fall of Imperial Russia and the Bolshevik seizure of power, the Russian Church found herself isolated and her dioceses outside Soviet Russia lost their support. Archbishop Meletios’ foundation of a purely Greek ethnic diocese in America became the first in a whole series of divisions which followed. As a result, various groups demanded and received the support of their national Churches (5).

After losing the see of Athens, in February 1921 Meletios set off for America. At that time, according to the decsion of the Sacred Episcopal Council of the Serbian Orthodox Church (SOC), Bishop (now Saint) Nicholas Velimirovic had been sent with a mandate ‘to investigate the situation, needs and wishes of the Serbian Orthodox Church in the United States’. In his report to the Sacred Episcopal Council on 13/26 June 1921, Vladyka Nicholas mentions meeting Meletios, also informing them that:

‘The position of the Greeks was explained to me best of all by the Metropolitan of Athens, Meletios Metaksakis, who is now in exile in America, and Bishop Alexander of Rhodes, whom the same Metropolitan Meletios sent to America three years ago and to whom he delegated duties as Bishop of the Greek Church in America.

Metropolitan Meletios considers that, according to the canons, the supreme oversight of the Church in America is to belong to the Patriarch of Constantinople. He quotes Canon 28 of the Fourth Oecumenical Council, according to which all churches in ‘barbarian’ lands belong to the jurisdiction of the Patriarch in Constantinople. In his opinion, this jurisdiction would be more honorary than anything else, and would be more real only in matters of appeal on the part of a dissatisfied party’ (6).

Naturally, this was interesting news for Bishop Nicholas and he mentioned it in his report to the SOC Council, because nobody until that time had interpreted Canon 28 of the Fourth Council in such a way. Not a single Patriarch of Constantinople until Meletios had yet tried to substitute a primacy of power for the primacy of honour, or some myth of supreme judgement in ‘matters of appeal by the dissatisfied party’ for the catholicity of the Church.

Apart from his work to establish completely new arrangements among the Local Churches and their diasporas, in America Meletios also showed great concern to develop exceptionally cordial relations with the Anglicans (Episcopalians). On 17 December 1921 the Greek Ambassador in Washington informed the authorities in Thessaloniki that Meletios, vested, took part in an Anglican service, bowed with the Anglicans in prayer, kissed their altar, preached and later blessed those present! (7).

When the Holy Synod of the Church of Greece learned of Meletios’ activities in November 1921, a special commission was set up with the task of investigating his situation. Meanwhile, while this investigation was ongoing, Meletios was unexpectedly elected Patriarch of Constantinople. The Synodal commission extended its work and on the basis of its conclusions on 9 December 1921 the Holy Synod of the Church of Greece expelled Meletios Metaksakis for a whole series of infringements of Canon Law and also for creating a schism (8). Despite this decision, on 24 January 1922 Meletios was raised to the Patriarchal see. And then, under strong political pressure, on 24 September that same year the decision to expel him was revoked.

Metropolitan Germanos (Karavangelis), who at that time had already been legally elected Archbishop of Constantinople, relates the following regarding the circumstances connected with the unexpected change of situation: ‘There was no doubt about my election to the Oecumenical Throne in 1921. Of 17 votes, 16 were for me. Then a layman known to me offered me 10,000 pounds if I renounced all my rights to the election in favour of Meletios Metaksakis. Naturally, irritated and annoyed I rejected the offer. Immediately after this a three-man delegation from ‘The National Defence League’ visited me one night and energetically persuaded me to renounce my election in favour of Meletios Metaksakis. The delegation told me that Meletios could obtain $100,000 for the Patriarchate, that he was on very good terms with Protestant bishops in England and America, that he could be very useful in Greek national interests and that international interests required Meletios to be elected as Patriarch. Such were the wishes of Eleutherios Venezelos.

All night long I thought about this proposal. Economic chaos reigned in the Patriarchate. The Greek government had stopped sending aid and there were no other sources of income. Salaries had not been paid for the last nine months. The charitable organizations of the Patriarchate were in a critical material situation. With these considerations in mind and for the sake of the welfare of the people I accepted the proposal (9).

After this agreement, on 23 November 1921, there was accepted a proposal of the Synod of the Patriarchate of Constantinople to postpone the election of the Patriarch. Immediately after this, the bishops who had voted to postpone the elections were replaced by others, so that two days later, on 25 November 1921 Meletios was elected. The bishops who had been removed met in Thessaloniki and issued a statement saying that ‘Meletios election was completely against the holy canons’ and they promised ‘to conduct an honest and canonical election of the Patriarch of Constantinople’ (10). Despite all this, two months later, amid general astonishment, Meletios nevertheless became Patriarch of Constantinople.

It may be said that from the moment that he was elected there begins a completely new chapter in the history of the Orthodox Church. As a fiery warrior for the political ideas of Panhellenism, an energetic modernist and Church reformer, Meletios initiated a series of reforms and influenced the acceptance of numerous resolutions which had extremely tragic consequences. In 1922 the Synod of his Patriarchate issued an encyclical which recognized the validity of Anglican orders (11) and, from 10 May to 8 June, at Meletios’ initiative a ‘Pan-Orthodox Congress’ took place in Istanbul.

Despite the resolutions of the Councils of 1583 (12), 1587 and 1593, the Congress took the decision to change the calendar of the Orthodox Church. It is remarkable that at this Conference, which goes under various names – ‘Pan-Orthodox Congress’, ‘Orthodox Assembly’ (13) and so on – representatives of only three Local Churches were present: from Greece, Romania and Serbia. At the same time representatives from others, and moreover from the closest – the Patriarchates of Antioch, Jerusalem and Alexandria - decided not to take part. As Oecumenical Patriarch, Meletios chaired the sessions of the meeting, at which the Anglican Bishop Charles Gore was present. At Meletios’ invitation, Gore sat on his right and took part in the work of the Congress (14).

It can be said that the introduction of the new calendar provoked extreme disappointment all over the Orthodox world, among parish clergy and laypeople, and above all among monastics. This gesture was taken as the visible sign of Constantinople’s intention to draw closer to the West to the detriment of the age-old liturgical unity of the Local Orthodox Churches. The so-called ‘Pan-Orthodox Congress’, consisting of representatives from three Local Churches, managed to accept the new calendar for the very same reasons of Unia, for which the preceding Orthodox Councils had condemned and rejected it: ‘For the sake of the simultaneous celebration of the great Christian feasts on the part of all the Churches’ (15).

Whatever and whoever this conference represented, historians will most probably be forced to recognize that it was one of the most tragic events in the life of the Church in the twentieth century. The agenda, set from above and forced onto people in contradiction with previous Conciliar decisions, introduced under political pressure the so-called new calendar. This caused schisms and bloody clashes in the streets, which Meletios himself did not escape. Meletios' modernist reforms of the Church were not to the taste of the faithful. In Istanbul there were serious incidents, during which the outraged Orthodox population sacked the Patriarch's apartments and physically beat Meletios himself (16). Soon after this, in September 1923, he was forced to quit Istanbul and renounce the Patriarchal throne.

Judging

by all this, Patriarch Meletios had ambitious plans and this small and

inglorious meeting looked at more than one problem. Apart from the issue

of changing the calendar, they also examined the question of whether to

reject a fixed Easter Day, priests and deacons marrying after ordination,

second marriages for priests, relaxing the fasts, transferring great feasts

to Sunday and so on (17). On the subject

of this meeting, Archimandrite (now often venerated as a saint) Justin Popovich wrote in his

presentation of May 1977 to the Sacred Episcopal Council of the SOC:

'The issue of preparing and holding a new 'Oecumenical Council' of the

Orthodox Church is not new and does not date back merely to yesterday

in our period of Church history. This question was already raised at the

time of the unfortunate Patriarch Meletios Metaksakis, the well-known

and presumptuous modernist, reformer and creator of schism in Orthodoxy,

at his so-called 'Pan-Orthodox Congress' in Istanbul in 1923'.

As Oecumenical Patriarch, Meletios gave special attention to attempts to completely reorganize relations between the Local Orthodox Churches in the world, especially with regard to their diasporas. His decisions, letters, tomos and encyclicals were not only controversial, but sometimes logically contradicted one another. Thus, refusing to recognize the autocephaly of the Albanian Orthodox Church on the pretext that the Orthodox population was a minority, Meletios, despite all the official documents issued by the Russian Church, recognized the separation of the Polish Church, which in exactly the same way was also a minority in Poland (18).

As Vladyka Nicholas Velimirovich said in his report, Patriarch Meletios attempted to extend the interpretation of Canon 28 of the Fourth Oecumenical Council and in some way seize not only the Greek diaspora, but also other national diasporas. For the first time in history, a Patriarch was trying to launch the Patriarchate of Constantinople into an absolutely uncanonical and scandalous administrative invasion campaign in other people’s countries and against other people’s flocks. Fr Zhivko Panev writes of this:

‘Without consulting the Synod in Athens, in 1922 he used his connections with the Greek diaspora in America and subordinated it to himself. In that year he issued a Tomos on the foundation of an Archdiocese in North and South America in New York, with three bishops, in Boston, Chicago and San Francisco. At the same time he also took steps to subordinate to Constantinople diasporas of other nationalities. The first step in this direction was made in 1922, when he appointed an Exarch for the whole of Western and Central Europe in London, with the title of Metropolitan of Thyateira. Following this Constantinople began to dispute the right of Metropolitan Eulogius to run Russian parishes in Western Europe.

On 9 July 1923 Meletios subordinated to himself the dioceses of the Russian Church in Finland in the form of an autonomous Finnish Church. On 23 August 1923 the Synod in Constantinople issued a Tomos about the subordination to Constantinople of the Russian dioceses in Estonia, in the form of an autonomous Church.

Presided by Meletios, the Synod in Constantinople decided that it was indispensable to form a new diocese for the Orthodox diaspora in Australia, with a Cathedral in Sydney, under Constantinople. This was done in 1924’ (19).

Thanks to Meletios’ activities the Serbian Church also clashed with the Patriarchate of Constantinople. It had its diocese in Czechoslovakia, for which on 25 September 1921 the Serbian Patriarch Dimitri consecrated bishop the Moravian Czech Gorazd Pavlik (shot on 4 December 1942 by the Germans and now canonized) (20). Despite this, on 4 March 1923, Patriarch Meletios consecrated an Archimandrite Sabbatius as ‘Archbishop of Prague and All Czechoslovakia’ and gave him Tomos No 1132 on the restoration of the ancient Archdiocese of Sts Cyril and Methodius, which he then placed under the jurisdiction of Constantinople (21).

Apart from the Autocephalous Albanian Church, which Meletios did not recognize, there were also Serbs who lived on Albanian territory and whose spiritual care was in the hands of the Serbian Church. The secretary of the Monastery of Dechani, Victor Mikhailovich, was consecrated on 18 June 1922 as Vicar-Bishop of Scutari. Meanwhile, the Patriarchate of Constantinople argued with the Serbian Church for many years over the question of jurisdiction in Albania. In the meantime, Uniat propaganda, spread directly by the Vatican was successful. Bishop Victor of Scutari underwent terrible hardships from which he was delivered on 8 September 1939, when he died. He was buried in the Monastery at Dechani at his request (22).

Meletios’ recognition of Anglican orders even provoked the indignation of the Roman Catholics. Meletios’ innovations in the Church caused outrage and anger and the new calendar even caused schisms. In Istanbul, on 1 June 1923, there gathered a large group of indignant clergy and laity, who attacked the Phanar with the aim of deposing Meletios and chasing him out of the City. However, Meletios held out in the exceedingly overheated atmosphere for another month, only on 1 July 1923 to quit Istanbul on the pretext of illness and the need for medical treatment. Later, under strong pressure from the Greek government and the intervention of the Archbishop of Athens, Patriarch Meletios finally resigned from his post on 20 September 1923.

Only three

Local Orthodox Churches at first introduced the new calendar, which had

been accepted at his insistence at the unfortunate congress in Istanbul

in 1923. These were Constantinople, Greece and Romania. It was not introduced

in others for fear of further disturbances and schisms and also because

of the strong negative reaction. The

Patriarch of Jerusalem declared that the new calendar was unacceptable

for His Church because of the danger of proselytism and the spread of

the Unia in the Holy Land. Probably the most serious opposition to the

new calendar came from the Church of Alexandria. There, Patriarch Photius,

after an agreement with Patriarchs Gregory of Antioch, Damian of Jerusalem

and the Archbishop of Cyprus, Cyril, called a Local Council, at which

it was decided that there was no need whatsoever to change calendars.

The Council expressed great regret that this issue was on the agenda,

pointing out that the calendar change represented a danger for the unity

of Orthodoxy, not only in Greece, but all over the world.

However, great changes were soon coming to the Patriarchate of Alexandria itself. After the Greek defeat of 1924 in Asia Minor at the hands of Kemal Ataturk, big changes took place on the Greek political and military scene. Then came population exchanges, as a result of which some 1,400,000 Greeks from Asia Minor were forced to resettle in Greece and some 300,000 Turks left Greece (23). After his resignation from the see of Constantinople and the stormy and fateful events there, Patriarch Meletios turned up in Alexandria, where, with political support, he was named second candidate for the see of the Patriarchate of Alexandria (24).

At

that time, Egypt was under British mandate and the Egyptian government

had the right to confirm the candidacy of either of the two candidates

who had been put forward. The government in Cairo dragged its feet on

the decision for a whole year, only on 20 May 1926, under British government

pressure, to confirm their choice of Meletios to the see of the Pope and

Patriarch of Alexandria. Not in the least discouraged by the Local Council

called by his predecessor, pretexting the unity of the Greek diaspora

with their homeland (the new calendar had already been introduced in Greece

under pressure from the revolutionary government), Meletios introduced

the new calendar in Alexandria too. Thus, supposed concern for the Greek

ethnic diaspora took precedence over concern for Church unity and the

decisions of previous Councils.

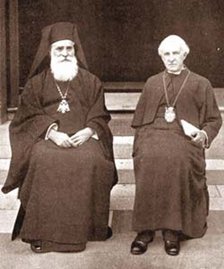

Metropolitan

Meletios and the Archbishop of Canterbury,

Cosmo Lang, at the Lambeth Conference in 1930

In 1930, as head of a Church delegation, Meletios Metaksakis took part in the Lambeth Conference (25), where he negotiated on unity between Anglicans and Orthodox.

Before Meletios Metaksakis died, this exile from the Holy Land, Kition, Athens and Constantinople, with his unstable, tireless and ambitious spirit, despite serious illness, tried to advance his candidacy for the see of Jerusalem. However, on 28 July 1935 he died and was buried in Cairo. In his wake there is still a stormy period, a restless time of political pressure and diplomatic intrigues, unacceptable in the Church of Christ, the consequences of which will be felt for many more years to come…

Priest Srboliub Miletich

Translated by Fr Andrew

14/27

June 2006

St Methodius, Patriarch of Constantinople

NOTES:

[1] Batistos D., Proceedings and Decisions of the Pan-Orthodox Council in Constantinople, May 10 - June 8, 1923, Athens, 1982

[2] One of them was the future Metropolitan Vasilios, an official representative of the Patriarchate of Constantinople

[3] Alexander I. Zervoudakis, 'Famous Freemasons', Masonic Bulletin, No. 71, January - February 1967

[4] Benedict Englezakis, Studies on the History of the Church of Cyprus, 4th - 20th Centuries, Vaparoum, Ashgate Publishing Limited, Aldershot, Hampshire, Great Britain, 1995, p. 440

[5] Metropolitan Theodosius, Archbishop Of Washington, The Path To Autocephaly And Beyond: 'Miles To Go Before We Sleep' http://www.holy-trinity.org/modern/ theodosius.html

[6] Bishop Nikolai Velimirovich, Collected Works, Vol. 10, 1983. p. 467 (In Serbian)

[7] Delimpasis, A.D., Pascha of the Lord, Creation, Renewal, and Apostasy, Athens, 1985, p.661

[8] Delimpasis, A.D., Pascha of the Lord, Creation, Renewal, and Apostasy, Athens, 1985, p.661

[9] Ibid., p.662

[10]Ibid., p.663

[11] Encyclical on Anglican Orders, from the Oecumenical Patriarch to the Presidents of the Particular Eastern Orthodox Churches, 1922, http://www.ucl.ac.uk/~ucgbmxd/ patriarc.htm

[12] The Local Council of 1583 in Constantinople was summoned in response to the proposal of Pope Gregory XIII to the Orthodox to accept the new calendar. Patriarch Jeremiah of Constantinople, Patriarch Sylvester of Alexandria, Patriarch Sophronios of Jerusalem and other fathers took part in the Council. The Council clearly said: If any do not follow the customs of the Church, founded in the Oecumenical Councils, including holy Pascha (Easter) and the calendar, which they command us to follow, but wish to follow the newly devised Paschalia and the calendar of the atheist astronomers of the Pope and contradict (the customs of the Church), wanting to reject and sully the dogmas and customs of the Church, which we have inherited from our fathers, may ANATHEMA be on them and may they be excommunicated from the Church and communion with the faithful.

[13] Sibev T., The Question of the Church Calendar, Synodal Publishing, Sofia, 1968, pp. 33-34 (In Bulgarian).

[14] The very name 'Congress' witnesses to the fact that this meeting does not fit in with Orthodox Tradition

[15] The Encyclical of the Patriarchate of Constantinople, 'To All the Churches of Christ', January 1920

[16] 'The Julian Calendar', Orthodox Life, No. 5, 1995, p. 26

[17] Hieromonk Sava (Yevtich), Ecumenism and the Time of Apostasy, Prizren, 1995, p. 11 (In Serbian)

[18] Priest Zhivko Panic. The Question of the Diaspora - A Historical and Canonical Review, Paris, Manuscript (In Russian)

[19] Ibid.

[20] Sava, Bishop of Shumadia, Serbian Hierarchs from the Ninth to the Twentieth Centuries, Belgrade 1996, pp. 135-135 (In Serbian)

[21] Serge Troitsky, Ecclesiastical Jurisdiction over the Orthodox Diaspora, Sremski Karlovtsy, 1932, p. 4 (In Serbian)

[22] Dr Dimsho Perich, The Serbian Orthodox Church and Her Diaspora, Istochnik, The Journal of the Serbian Orthodox Diocese in Canada, 1998, No. 38

[23] ‘In the twentieth century the Greek population of Turkey underwent terrible persecutions and genocide. In 1920 in Istanbul alone there were about 100,000 Greeks. After the First World War and the Greek defeat at Smyrna (Izmir) in 1922, the Greeks there suffered a real disaster - ‘the great disaster’. The Greeks of Asia Minor fled and resettled elsewhere. This happened after the signing of peace in Lausanne in Switzerland in 1923. After this only an insignificant number of Greeks remained in Istanbul and of Turks in western Thrace. At the present time there are about 4,000 Greeks in Istanbul’. Archpriest Radomir Popovich, Orthodoxy at the Turn of the Centuries, Belgrade, 1999, p.23 (In Serbian)

[24] The first candidate was Metropolitan Nicholas of Nubia

[25] The Conference of all the Anglican Bishops which takes place every ten years in the Palace of the Archbishop of Canterbury. It looks at questions of faith, morality and order in the Anglican Communion