A

Contemporary Church Father:

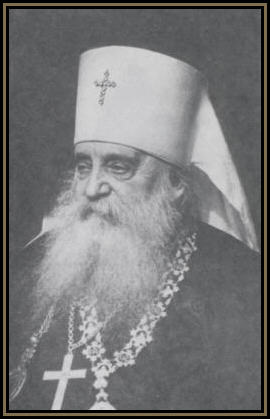

Metropolitan Antony of Kiev and Galicia (1863-1936)

Remember them which have the rule over you, who have spoken unto you the word of God; whose faith follow, considering the end of their conversation

Hebrews 13,7

Foreword

Next year, 2006, will mark the seventieth anniversary of the repose of His Beatitude Metropolitan Antony (Khrapovitsky) of Kiev and Galicia, one of the most outstanding Orthodox hierarchs and theologians of the twentieth century. It is unthinkable that this anniversary could pass unremarked. It was Metropolitan Antony who fought for the return to the theology of the Church Fathers, for restoration of the canonical order of the Patriarchate of the Russian Church and for the establishment in unity and freedom of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia. As the Serbian Patriarch Barnabas said of Metropolitan Antony at his Jubilee in 1935: ‘Tongue cannot describe your great deeds. You are a pillar and foundation of truth in the Church of Christ. Your heart embraces all Orthodox people…You shine forth to the Russian people at this time when Holy Russia is being redeemed by the blood of its best sons and your light is no less precious than that holy blood which is shed in the Russian land’.

Against all odds, against the erastianism, decadent careerism and narrow chauvinism widespread in the Russian Church before the Revolution, against the anti-clericalism of the Kerensky government of 1917 and later their representatives in the emigration, against the militant atheism of the Bolsheviks and their renovationist puppets, against extremists of all sorts, Metropolitan Antony, inspired by the Holy Spirit, stood for the Church and Orthodox Tradition, always ready for martyrdom. Now, nearly three generations after his repose, when his works are at last being published in contemporary Russia, we believe that the Orthodox world will soon be looking to his canonization. For very often, the true greatness of the saints of the Church is revealed to fallen humanity only three generations after their repose. This is when humanity comes to understand their prophetic sacrifices, the sacrifices of such figures as Metropolitan Antony.

Alexis,

Child of God (1863-1885)

Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

Matthew 5,3

The future Metropolitan Antony of Kiev and Galicia was born on 17 March 1863 in the village of Vatagino near Novgorod. Born on the feast-day of St Alexis of Rome, the Man of God, his devout parents naturally called him Alexis. His father belonged to the noble Khrapovitsky family, his mother, a very pious woman, came from minor nobility near Kharkov. The child Alexis soon learnt an appreciation for religious books from his mother. At a young age he read of the Monastery of Optina and, aged seven, conceived the desire to become a monk, a desire which never wavered in him from that moment on. He was also much impressed by the ancient churches and monasteries of Novgorod and was disappointed to discover that although other Orthodox Churches had Patriarchs, there was now, mysteriously, no Patriarch in Russia.

When Alexis was still a child, the Khrapovitsky family moved to St Petersburg and here Alexis was also impressed by Church life. As a young child he often served in the altar and met, among others, a famous missionary, the future St Nicholas of Japan. He even gave up his pocket money to contribute to missionary work abroad. Aged nine, Alexis started school. He at once disliked the system whereby teachers treated pupils as enemies. However, he studied brilliantly and was popular with other children for his friendliness, kindness and humanity. He was different from the other boys in that he was serious, never going to dances and disliking theatres. His real interest was the Church, so much so that even at this young age he wrote a service to Sts Cyril and Methodius in Church Slavonic, a service which was later approved by the Holy Synod and used in Church services. At this time Alexis also learnt to like literature, especially Dostoyevsky, whose Orthodox values he appreciated.

On leaving school at 18, Alexis did not want to continue his studies and become a lawyer or civil servant, as his parents wished. Instead, he chose the way of the Church. Despite his parents’ initial opposition, he went to study at the St Petersburg Theological Academy. Here Alexis met some of the keenest minds of Europe, academic theologians who were famed well outside Russia. These professors were not only theoretical academics, but they lived their Orthodoxy, combining deep faith with patriotism. From the beginning Alexis, with his friendly and sociable nature, showed exceptional talent and made a great impression on other students, showing himself to be a born leader. He took especial care of the church in the Academy, even collecting funds for its improvement and adornment. In particular, having obtained special permission, he started the custom for students to preach sermons. Alexis’ own sermons were particularly outstanding. In his third year, new staff at the Academy attracted the students to monastic life and Alexis was naturally among these students.

Fr Antony (1885-1897)

Blessed are they which hunger and thirst after righteousness, for they shall be filled.

Matthew

5,6

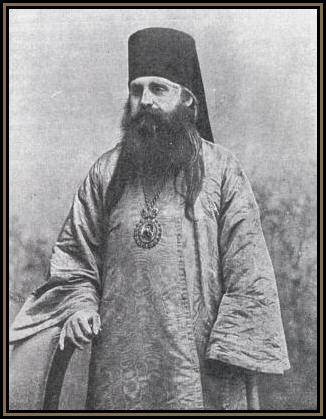

On graduating in 1885, and despite opposition from parents and others, Alexis became a monk. He was aged only 22. Taking the name Antony, after the Novgorod St Antony the Roman, he was ordained deacon soon after. Three months after this he was ordained priest and appointed deputy inspector of the Academy. Fr Antony displayed his basically monastic view that the Academy, like any school, should be more a community, that the students were not subordinates who had to be tested and ‘found out’ through exams, but brothers. He never condoned student pranks, but instead through his own example showed the students how to behave.

However, seeing his closeness to the students, he was asked by the authorities to denounce students. This he refused to do and he asked to be transferred elsewhere. Fr Antony found himself transferred, or perhaps rather exiled, to a small and new seminary, of Uniat origins, in Kholm, a half-Polish town in the far west of the Russian Empire. In all he spent one year here before he was called back by a new Rector, who recognized his wasted qualities.

Fr Antony was now called on to teach Old Testament and later served as Inspector of the Academy. One of his main interests, as ever, was the possibility of fulfilling his childhood dream – to see a Patriarch at the head of the Russian Church, in other words, to restore canonical order to the Church in Russia. He attracted little sympathy from the conservative, but anti-Tradition, authorities for this, who saw in him a kind of radical reformer. However, he did attract many students to the monastic life. Interestingly, among them was a certain Basil Belavin – the future Russian Patriarch. The Academy also received visits from the future St John of Kronstadt, whom Fr Antony loved. Fr Antony often served and also loved to preach. He taught that sermons are only effective when they come from the heart, when they are sincere. His own sermons always were. In 1889, still aged only 27, Fr Antony became Rector of the Academy and was raised to the rank of Archimandrite. Never before had such a young man been appointed to this position.

This position in St Petersburg was to last for only one year, for in 1890 he was appointed Rector of the Moscow Theological Academy. Here, too, Fr Antony showed his characteristic humility, self-sacrifice and compassionate love for the students. His door was open to all, he was like a father to all, who gave both trust and respect to this priest who showed them the example of love. Fr Antony chose to teach Pastoral Theology here, a subject then much neglected. In 1893 the Academy received a visit from the future St John of Kronstadt, who miraculously healed Fr Antony of sickness. The example of Fr Antony led to a huge improvement in student life. Drunkenness among the students, until then rampant, ceased, and academic and spiritual life improved, many students became priests or monks. In a word, the Academy became a sort of spiritual centre, attracting not only Muscovites, but others from elsewhere in Russia.

However, in 1893, a new Metropolitan of Moscow was appointed and Fr Antony’s troubles began. The new Metropolitan began to interfere in the Academy and made demands which Fr Antony refused to meet, as they were negative for student life. Fr Antony was ‘punished’, by being transferred to the Kazan Theological Academy, where he spent one year, from 1895-6. Within two months, Fr Antony had here too become popular, winning hearts, and was appreciated and loved by the professors and the students alike. Again, he invited groups of students to drink tea with him in the evenings and long discussions on Church themes took place, especially the theme of restoring a Patriarch. Many students were drawn to monasticism here. Fr Antony continued to teach Pastoral Theology in an inspired way, teaching that the ideal pastor is the monastic Elder.

Bishop

Antony (1897-1906)

Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the earth.

Matt 5,5

In September 1897, aged only 34, Archimandrite Antony was consecrated a vicar-bishop of Kazan, while remaining Rector of the Academy. However, in 1900, Bishop Antony of Chistopol (which was then his title) was appointed Bishop of Ufa. He left the Academy and began life as a diocesan bishop.

Ufa was the centre of a province of over 2,500,00 people, of whom 840,000 were Orthodox and the rest Muslims, Old Believers or pagans. Priests were few, ill-educated and extremely poor. There was only priest for every 2,500 faithful. Services according to the Typikon began, Bishop Antony served and preached every Sunday, giving talks afterwards. His Cathedral was crowded with thousands of faithful who came to pray and hear their new, energetic, young bishop The Christmas service began at 1.00 in the morning – the Cathedral was filled. He visited the most distant parishes. Some of Bishop Antony’s disciples, educated monks, came to help him revive his diocese. People came from all over Russia to provincial Ufa.

In Bishop Antony’s brief time in Ufa, the number of parishes doubled, the number of priests increased considerably. Notably, the Bishop ordained native, non-Russian clergy as second priests in the parishes. He also conducted missionary work among the Muslims. Although Bishop Antony would have been happy to stay in Ufa for the rest of his life, in 1902, less than two years after his appointment, he was sent to be Bishop of Volhynia and Zhitomir, at the other end of Russia.

Bishop Antony was to stay here for twelve years. The population of Zhitomir was composed of 60,000 Jews, 20,000 Polish Roman Catholics and only 20,000 Orthodox, served by only ten Orthodox churches, as against 60 synagogues. Roman Catholic propaganda was strong and Orthodox life decadent. Two Roman Catholic bishops, both educated and devout, lived in the town. Protestant sectarianism and the Old Believers were also active. However, the Diocese of Volhynia was the biggest in Russia for the number of its churches.

Bishop Antony began his task by calling his people back to their roots, of the newly-baptized Russia of St Vladimir nearly 1,000 years before. Then he eliminated corruption and bribe-taking in the diocesan administration, before proceeding to missionary work. Once more he introduced Cathedral services conducted according to the Typikon, thus setting a standard or example for the whole diocese to follow, according to ability. He also encouraged the veneration of St Anastasia the Roman, whose head was placed in a shrine beneath the Cathedral to counter the Roman Catholic feast of Antony of Padua.

He attempted to end the decadent Polish Catholic influences among his clergy, influences of clericalism, which separated clergy from their flocks merely on account of their different educational levels. He wanted the clergy to return to Orthodox practices, the practices of the Good Shepherd. He opened his doors to all, saying that he was the bishop of the Russian peasants, not the bishop of the Polish lords and the bourgeois. To all he was a father. He attracted the clergy back to the services, the Typikon, the sign of the cross, prostrations, the Lives of the Saints, away from the ugly theatrical, Italianate services and the half-Lutheran, half-Catholic religion that had prevailed before. Soon his influence began to have an effect.

Bishop Antony built a huge hall, holding 1,000, for missionary work and discussion. It was often full. He encouraged Church processions as part of Orthodox missionary witness. He opened a seminary to encourage new clergy, and a school for deacons, catechists and choir directors. He opened hundreds of Church parish schools, so that eventually there were over 1,600 in his diocese, twice the average number of other dioceses.

In 1905, when Russia was swept by a Revolutionary movement, Bishop Antony made crystal clear his position: whatever the failings of the present government, the removal of the Tsar would be catastrophic. Though mocked at that time, twelve years later his prophetic declamations were all to prove correct in every single detail. He was much attacked for these prophecies by the anti-Christian liberal intelligentsia, half-baked intellectuals like Struve and Berdiaiev, who were undermining Russian society, and who later created the emigre schism in Paris under Metropolitan Eulogius.

Archbishop Antony (1906-1917)

Blessed are the merciful, for they shall obtain mercy

Matthew 5,7

In 1906, Bishop Antony was made Archbishop of his diocese. He was just 43 years old. The Archbishop did much to improve life at the chief monastery in his diocese, the great Lavra of Pochaiev, which was under the wise leadership of Archimandrite, later Archbishop, Vitaly. A common method used by the anti-Christian intelligentsia to attack the Church at this time was slander, accusing Archbishop Antony of anti-semitism. The reality was just the opposite. In fact he defended the Jews from pogroms, organized by unchurched Cossacks and others. Despite Jewish provocations and profiteering, pogroms did not occur in Archbishop Antony’s diocese in the year of pogroms, 1903, and none from 1906, although fights occurred in 1907, when the Archbishop was absent in St Petersburg. Indeed, on this occasion the Jews accused the government of calling the Archbishop away, because otherwise, in the Archbishop’s presence, the government knew that no pogroms would occur.

Until the time of Archbishop Antony, Pochaiev Lavra had been idiorrhythmic, indeed it had largely been in a state of decadence and provinciality. The monks were even allowed to eat meat. The Lavra was transformed under Archbishop Antony and the services were conducted properly. It started to become coenobitic, with 360 monks in all. Three sketes were built, the relics of St Job of Pochaiev were honoured with a new feast, tens of thousands went on pilgrimage and the Archbishop himself lived there for much of the year. He was its first monk. The Archbishop also built a new church in the Lavra, dedicated to the Holy Trinity, which could contain 2,000. It was consecrated in 1912. The Archbishop composed two services, one to the Pochaiev Mother of God, the other to St Job. Archbishop Antony also restored two other ancient churches in his diocese.

In 1911, while the Archbishop was in St Petersburg, a former student of the Kazan Academy attempted to assassinate him with a dagger. He failed, but interestingly at his trial the former student declared why he had done this: he had doubted in God and had wanted to see if God existed. If God would save the ‘best Bishop in Russia’, then it would be clear that God really existed. The Archbishop, unperturbed, received some 200 telegrams of sympathy. Patriarch Damian of Jerusalem wrote a telegram, declaring that God had preserved a precious life, ‘so necessary for the good of the Church’. However, anarchist groups also threatened the Archbishop, who fearlessly invited them to try to murder him, saying that ‘it is better to die than to see such iniquity’.

At this time many wondered why Archbishop Antony had not been given a more important see, that of St Petersburg or Moscow for example, rather than being left in the outer provinces. It was not to be, for those in power were opposed to the fearless and frank-speaking Archbishop. Liberal circles and courtiers were frightened of the uncompromising Orthodoxy of the Archbishop and his desire to restore a Patriarch. In this, the anti-Church lobby saw a threat to their worldly pretensions and their 200 year-old enslavement of the Church. They slandered and intrigued accordingly. Archbishop Antony, however, always remained faithful to his conscience and spoke the truth to all, small and great alike.

In 1913, Archbishop Antony was instrumental in arranging the visit to Russia of Patriarch Gregory IV of Antioch. Archbishop later said that this moment greatly helped lead to the restoration of the Patriarchate in Russia. Another achievement of the Archbishop was the protection of the persecuted Carpatho-Russian Orthodox, then living in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Here the Archbishop involved himself in the struggle against the spiritual fraud of Uniatism, so encouraged by the Austro-Hungarians. In this he had to overcome the prejudices of Russian society which saw in Roman Catholicism just a variant branch of Christianity, instead of a heresy that had fallen away from the Church. He understood that the root of this was the failure of theological education in Russia, which needed to return to the Patristic understanding of Orthodoxy, instead of copying Roman Catholic and Protestant manuals, as it had done since the late seventeenth century.

In order to protect the Carpatho-Russians, Archbishop Antony turned to the Patriarch of Constantinople, Joachim III, and asked him to take pastoral care of them. He at once accepted to do this, appointing Archbishop Antony as his Exarch for Galicia and Carpatho-Russia. Archbishop Antony was alone in protecting this people from the ever-increasing oppression of the Austro-Hungarians and Roman Catholics. Seeing increasing numbers of them returning to Orthodoxy from Uniatism, in May 1914 Austro-Hungarian diplomats contacted St Petersburg and, through their political intriguing, had Archbishop Antony transferred to the east as Archbishop of Kharkov.

Kharkov had a population of nearly 200,000 Orthodox, with five monasteries and five convents. The most famous of these was the Sviatogorsk Monastery with 600 monks, famed for its strict and holy life. As usual, Archbishop Antony’s first act was to improve the quality of liturgical life in his diocese. As usual, his doors were open to all. In particular, theological students were attracted to his loving heart, as well as old friends from Volhynia and the Theological Academies. Already by 1908, his ex-students had included two Archbishops, 35 bishops and countless hieromonks, many of whom were later to become bishops. Many of these were later to be martyred by the Communists.

When in 1914 the Austro-Hungarians, backed by the Germans, started the First World War, Archbishop Antony behaved as a patriot. He was often to be seen visiting the sick in hospitals. Thanks to the Archbishop’s command of German, he was able to comfort German and Austrian prisoners too. When military reverses began, the Archbishop was in the forefront of taking refugees from the west. In January 1917, he took in refugees from war-torn Serbia, notably another former pupil, Bishop Barnabas, who was later to become the Serbian Patriarch, just as previously, in Pochaiev, he had once received the Serbian Metropolitan Dimitri, who also became Patriarch. This was characteristic of Archbishop Antony’s truly universal personality, for he paid no attention to nationality, only to Orthodoxy.

In March 1917 came the first Revolution and the abdication of the Tsar. Talk began among the intolerant liberal revolutionaries of arresting the Archbishop. Fearless, the Archbishop declared that ‘equality’, proclaimed by the revolutionaries, was not the answer to social questions; what was important is love. In April the revolutionaries expelled the Archbishop from Kharkov. In making his farewell, the prophetic Archbishop advised all to keep Holy Tradition and the canons of the Church.

The Archbishop chose as his place of exile the Monastery of Valaam, in the north of Russia. Here he lived as a simple monk and also wrote his great work on the Dogma of the Redemption, his attempt to free the Russian theology of the Redemption from its Roman Catholic captivity and return it to the Patristic heritage. However, here he was called on to take part in the All-Russian Church Council, which was then being prepared in Moscow. At the same time, the people of Kharkov unanimously called back the Archbishop to be theirs once more. The civil authorities were forced into accepting the demands of the people and the Archbishop was triumphantly greeted in Kharkov.

On 15/28 August 1917 the Moscow Council opened. Although there were many Church-minded delegates, there were also extreme right-wing ones and extreme left-wing ones, sent there by Kerensky’s anti-Church Provisional Government. The battle of Archbishop Antony and the other true churchmen, the many younger bishops and monks, was against the conservatism of the right and the renovationism of the left, in favour of the canons, the Tradition of the Church. The Archbishop and his allies were most active at every step.

The greatest battle was for the realization of the Archbishop’s childhood dream – the restoration of canonical order in the Russian Church, the return of the Patriarchate, the return to the path of the Fathers. The Provisional Government, dominated by freemasons, had even called the Patriarchate ‘anti-Christian’ and was rabid in its determination to see the Church remain a slave of secular government, to be the victim of its own modernism.

In this it failed. In October (old style), the Provisional Government, as was inevitable, was swept away by the Bolsheviks, as we would say now, into the dustbin of history. On the other hand, a Patriarch was elected. There were three candidates. In the first round, out of 273 votes, Archbishop Antony received the most, 101, votes. From the three final candidates, the holy Hieroschemamonk Alexis drew lots; the lot fell on Metropolitan Tikhon of Moscow. Archbishop Antony called the election an act of Divine Providence, as indeed it would turn out to be. One of the first acts of the new Patriarch was to make the five most senior Archbishops of the Russian Church Metropolitans. Among them was Archbishop Antony.

Metropolitan Antony in Russia (1917-1920)

Blessed are they which are persecuted for righteousness’ sake, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven

Matthew 5,10

The new Metropolitan returned to Kharkov, but after Easter 1918 rumours circulated that he was to be appointed Metropolitan of Kiev and Galicia, to replace the martyred Metropolitan Vladimir. Despite the opposition of the faithful flock in Kharkov, these rumours turned out to be true. The Metropolitan himself knew that the new position would be Golgotha, but accepted his cross, since his new responsibility was also for Galicia and his beloved Carpatho-Russia.

The Ukraine at that time was controlled by Ukrainian nationalists and the Germans. The nationalist-separatists created a schism. The Germans on the other hand had great respect for the Metropolitan, who spoke excellent German. At once in Kiev the new Metropolitan began giving talks and making clear his pastoral concerns. However, in December 1918, he was arrested by Ukrainian separatists. Despite protests by crowds of the faithful, who were dispersed by cavalry, the Metropolitan was taken under house arrest to Tarnopol in Galicia and then imprisoned in the Uniat monastery of Buchach.

Here, in captivity, for five months he composed services and wrote on theological topics. Then the region was invaded by the Poles. Polish soldiers threatened their prisoner with death, but a Polish officer showed the Metropolitan respect, rescuing him. He was taken to Krakow where he was interviewed by an aristocratic Polish Cardinal, the Metropolitan conversing fluently with him in Latin. The Metropolitan accused the Poles of treating him as a criminal. He was escorted back to the monastery.

He was finally freed in August 1919, when Kiev was liberated by the White Army. The Metropolitan was not able to return to his see directly, but had to travel via Constantinople. In September the Metropolitan returned in triumph. However in October the Red Army advanced again. The Metropolitan was threatened with death from a hostile crowd of Bolsheviks. Fearless of death, he defied them and he was released. With the Red Army advancing, the Metropolitan was persuaded with difficulty to leave Kiev, but he returned again as soon as the Communists were chased out. But soon after, while he was on urgent Church business in the south, Kiev was occupied again, and this time for good. The Church authorities sent the Metropolitan to Ekaterinodar in the still free south of Russia and from there to Novorossisk on the Black Sea.

Here mass evacuation took place, as Communists shells began to land and gunfire could be heard. The Metropolitan refused to leave. However, on 12 March 1920 he was tricked into going on board a ship to conduct a service ‘to thank God that the Greeks had taken St Sophia in Constantinople’ – which had of course not happened. Before he could start any service, the ship had weighed anchor and the Metropolitan realized that he was in effect being abducted – for his own safety.

That Easter the Metropolitan was in Athens, serving with the Greek Metropolitan, after which he went to Mt Athos and spent five months at St Panteleimon’s Russian Monastery. There in September 1920, he received a telegram from the White Army calling him to the Crimea. He at once set out for the Crimea, but was only to spend some forty days in Sebastopol. The White cause had finally been lost. The White Army was evacuated, the Metropolitan with it. 125 ships sailed with some 150,000 people, 27,000 women and children, bishops, generals, academics, fleeing the murderous Red Army. The Metropolitan, like nearly all of these refugees, was never to set foot in Russia again.

Metropolitan Antony In Exile (1920-1936)

Blessed are ye, when men shall revile you, and persecute you, and shall say all manner of evil against you falsely, for my sake.

Matthew 5,11

At first, Metropolitan Antony, the senior Russian Bishop outside Russia, believed that Russians in exile should organize themselves under the Local Orthodox Churches, wherever they were. However, seeing the scale of the emigration, he was soon persuaded that there should be some united Church organization of the Russian exiles. Since there was a canonical precedent (Canon 39 of the Sixth Oecumenical Council), in November 1920, the exiled Russian bishops met and agreed on this arrangement. This decision was confirmed by Patriarch Tikhon in Moscow and also by the Patriarchate of Constantinople on 22 December, with Metropolitan Antony, the senior bishop, at the head of the ‘Higher Church Authority’.

This was the canonically-established organization which had dealt with Russian Orthodox in the south of Russia, who had been cut off from Patriarchate Tikhon in Moscow by political and military events. It now found itself outside Russia, but no change was made to this arrangement, because most at that time still thought that they would soon be returning to Russia. The Metropolitan now stayed for three months in Constantinople, rejecting the offer of the Patriarch of Antioch to go and live there, and also refusing a generous salary from the Roman Catholics. The Metropolitan made it clear that he wanted to share the lot of the three million other Russian exiles.

So began the organization of Church life for the worldwide Russian emigration, in the Far East, in Europe, in Jerusalem, in the Americas, in Australia. In the spring of 1921 the Higher Church Authority finally established its centre in Sremski Karlovtsy in what was to become Yugoslavia. In November that year there took place its first Council. Eleven bishops gathered under the chairmanship of Metropolitan Antony. Soon after this Council, the Serbian Patriarch Dimitri, on whose territory the Council had taken place, received a telegram from Patriarch Tikhon in Moscow, thanking him for his aid in helping this émigré Russian Church. The Bishops outside Russia felt encouraged.

In 1922, following new instructions from Patriarch Tikhon in Moscow, the bishops in exile decided to dissolve the former ‘Higher Church Authority’, originally designed for bishops inside Russia, but cut off from the Patriarch in Moscow, and rename it ‘The Synod of Bishops of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia’. Also in 1922 the Metropolitan appealed to the civilized world for intercession for Russia, when Patriarch Tikhon was arrested by the Communists in Moscow and the Communists set up their ‘Living Church’ schism, a yet more subtle way of ‘dividing and ruling’. The Metropolitan received much support from the Protestant world and also from right across the Orthodox world. Thus, thanks to foreign intervention, the Soviet government would stop short of murdering Patriarch Tikhon and freed him.

Unfortunately, in this same year a member of the exile Church, Metropolitan Eulogius in Paris, under indirect pressure from Communists in Russia and direct pressure from freemasons in the emigration (those who had supported the overthrow of the Tsar and the March 1917 Revolution), threatened a split in the exile Church. In order to avoid any such split, at the end of 1922 the Metropolitan decided to retire to Mt Athos and live there as a simple monk, taking the schema, rather than be used as an excuse for a division. However, he was told that the faithful would pray before the Miracle-Working Kursk Root Icon, asking the Mother of God to stop him from leaving. This indeed happened, for he was at the last moment refused authorization to go to Mt Athos. The feared split was not yet to take place.

In 1924, the Soviet government managed, perhaps through bribery or other political means, to set a now modernistic Patriarchate of Constantinople against Patriarch Tikhon. In this way they obtained their recognition of the schismatic and renovationist ‘Living Church’ and suspended Patriarch Tikhon. Seeing the clearly politically-motivated and astoundingly uncanonical interference in the internal affairs of another Orthodox Church by a newly corrupted Patriarchate of Constantinople, Metropolitan Antony stood up on behalf of the thirty-two Russian bishops in exile he represented, and defended the Patriarch. He also opposed the uncanonical modernist and new-calendarist Renovationist movement, which was then taking hold in Constantinople, as it was trying to take hold in Russia.

In April 1924, the new Patriarch of Constantinople, Gregory VII, tried to keep the Metropolitan a prisoner on Mt Athos, which he was visiting, forbidding him to travel, and then ordered Patriarch Dimitri of Serbia to close down the Church Outside Russia. The Serbian Patriarch naturally rejected this. The Church Outside Russia was now being persecuted from two sides, by the Communists in Russia and the Communist-orchestrated Renovationists, who had seized power in Constantinople. In his opposition to modernism the Metropolitan received the full backing not only of the Serbian Church, but also of the Patriarchs of Antioch, Jerusalem and Alexandria, who still completely adhered to the Orthodox Tradition. They all rejected the political reforms and uncanonical acts of the group of modernists who had seized power in Constantinople.

In October 1924, at the Fourth Council of the Synod of Russian Bishops, the careerist but weak Metropolitan Eulogius openly declared his disagreement with the other twenty-seven Russian bishops. Spurred on by Russian freemasons and St Petersburg aristocrats in Paris, politically-minded intellectuals purposely released from Soviet Russia to cause division in the emigration, and the Protestant-financed YMCA, from this time on Metropolitan Eulogius began to prepare in detail his Paris Schism, mentioned above. This was to take place formally in June 1926, when he simply walked out of the Council of Bishops, not having obtained what he wanted. This was the ‘victory’ of those who backed the Paris Metropolitan, left-wing intellectuals like Struve, Berdiaiev, Kerensky and Fedotov, who had supported the March 1917 Revolution in overthrowing the Tsar. At the same time the Russian Metropolitan Platon, in North America, also split away from the Russian Church, like Metropolitan Eulogius, seeking independence and power. Both these Metropolitans were suspended by the Synod of Bishops.

It was at this time that the persecutions in Russia also worsened, with most of the bishops inside Russia now martyred or else imprisoned. In 1927, one of the most senior of them, Metropolitan Sergius (Stragorodsky) was suddenly freed by the Soviets, became effectively the head of the official Russian Church, and issued his notorious ‘Declaration’. In this he praised the Soviet authorities and called for all Russian clergy outside Russia to sign a written document of complete loyalty to the godless Soviets. Metropolitan Antony called a Council of the Bishops in exile and they wrote a unanimous reply rejecting this purely political Declaration and its demands. This event was especially painful for Metropolitan Antony, since Metropolitan Sergius had been a pupil and personal friend in the old days. Everybody understood that Metropolitan Sergius was acting under intolerable duress.

In 1929, the Soviets invaded part of China and massacred Russian exiles there, committing the most atrocious barbarities. Again, fearlessly, Metropolitan Antony tried to direct the world’s attention to these atrocities. The Metropolitan, now ageing, showed that his loving heart was being torn apart, that he was crucified by these events, persecutions and divisions. He received popular support in England, France and Czechoslovakia, but this was not enough.

In 1930, persecution inside Stalinist Russia increased again and Metropolitan Sergius continued to lie. The latter even fell out with Metropolitan Eulogius in Paris, who had gone to the jurisdiction of Metropolitan Sergius, after breaking with the Church Outside Russia. Metropolitan Eulogius, refusing to return to the canonical exile Church, sought refuge under the modernistic Patriarchate of Constantinople, altogether leaving the Russian Church. Patriarch Barnabas called for unity among the Russians, saying in 1930: ‘In your midst there is a great hierarch, Metropolitan Antony, who is an adornment of the Universal Orthodox Church. His is a high mind, who is like the first hierarchs of the Church of Christ at the beginning of Christianity. In him is Church truth and those who have separated, must return to him’.

In 1933 the Soviets again tried to destroy the Church Outside Russia through their puppet, Metropolitan Sergius. In a letter to the new Serbian Patriarch Barnabas, he threatened all the free Russian Bishops with suspension and even threatened the Serbian Patriarch. Patriarch Barnabas, perfectly understanding the situation, ignored this letter, but Metropolitan Antony replied, pleading with his former pupil and friend, Metropolitan Sergius, to repent.

Now aged seventy, Metropolitan Antony was growing physically weaker and weaker. Exile was permanent suffering for him and there was little doubt that his life was being shortened by the Soviet-fostered division in the exile Church. His suffering had begun in 1927, as he saw Russia crucified and divisions in the emigration. Seeing his life coming to an end, the Metropolitan wrote to Metropolitan Eulogius in Paris, who despite being suspended by the Russian Church, had continued to act as a Diocesan Bishop. Metropolitan Antony begged him to come to Belgrade so that they could be reconciled. In May 1934 Metropolitan Eulogius did come and asked forgiveness. It seemed as though unity had been restored. Unfortunately, as soon as the weak Metropolitan Antony had returned to Paris, he again fell under the spell of his entourage and broke communion. On the other hand, Metropolitan Theophilus in North America, whose predecessor, Metropolitan Platon, had also broken off from the Russian Church, did restore canonical links at this time. Here at least there was the comfort of reconciliation.

In 1934 Metropolitan Antony consecrated a bishop for the last time. This was a young and remarkable man he had first met in Kharkov in 1914, and whom he had made a monk in 1926. This was the future St John of Shanghai, in whose consecration took part yet another great man of God and contemporary Church Father – the future Serbian saint, St Nicholas of Zhicha. Metropolitan Antony appointed Bishop John to be Bishop of Shanghai, as he wrote, ‘as my own soul, as my own heart’. Bishop John was to repose in holiness in San Francisco in 1966 and then be canonized in 1994.

1935 saw Metropolitan Antony’s jubilee, fifty years of service in the clergy. There was a great celebration, present were Russian bishops, the Serbian Patriarch and Metropolitan Elias of Mt Lebanon from the Patriarchate of Antioch. By this time the Metropolitan was no longer able to walk and used a wheelchair. His conversation was centred on spiritual matters, on the heart which acquires the Holy Spirit, on the joy of the Resurrection, on Communion, repentance and tears. On 15/28 July 1936, weeping he gave his last sermon. In it he said that only tears of repentance could return the crucified homeland. On 8 August (new style) the Metropolitan received the sacrament of holy unction. Two days later he reposed, at 9.20 in the evening of 28 July/10 August 1936.

The funeral took place on 13 August in the Cathedral of St Michael in Belgrade. Patriarch Barnabas, six bishops and dozens of priests concelebrated. In his funeral oration the Patriarch again compared the Metropolitan to the great bishops of the first centuries. The body of the Metropolitan was laid to rest beneath the Iveron chapel in a new cemetery, where the Metropolitan had some years before prepared his place. Here his earthly remains rest to this day.

Afterword

If God be for us, who can be against us?

Romans 8,31

My personal discovery of Metropolitan Antony’s works took place twenty-five years ago, when I was a young theological student. Reading through the volumes of his works, I said to myself: ‘But this is what I have always believed – though I could never have expressed even a hundredth part of this’. The above is merely a short sketch of Metropolitan Antony’s life for English-speaking readers, a small thank you to the influence of the Metropolitan on my life. The seventeen volumes, totalling 6,000 pages, of the Biography and Works of Metropolitan Antony by Archbishop Nikon (Rklitsky), as well as books of letters, sermons, articles and translations tell a much fuller story. Probably, however, the story of the Metropolitan’s noble soul, thoughts, words and deeds, will never be told in full in this world.

Some have reproached the Metropolitan for his frankness, his lack of diplomacy. But who has ever heard of a Church Father who was a diplomat? Did St Nicholas behave as a diplomat when he struck the blaspheming Arius at the First Oecumenical Council? Did St Athanasius and St Cyril of Alexandria behave as diplomats with the Arians? Did St Ambrose of Milan behave as a diplomat with a wicked Emperor? Did St John Chrysostom behave as a diplomat with the wicked Empress? Did St Leo the Great behave as a diplomat in his Christology? Did St Maximus the Confessor, St Gregory Palamas or St Mark of Ephesus behave as diplomats in opposing evil and telling God’s Truth? Metropolitan Antony only behaved as they did.

Others have reproached Metropolitan Antony for the way in which he expressed his theological views on the Redemption, absurdly accusing him of ‘stavroclasm’. But, distorting his views, they have overlooked the fact that the author was writing in reaction to the dreadful and blasphemous Roman Catholic satisfaction theory, which had completely taken over the Orthodox theology of the Redemption in Russia at that time. The Metropolitan merely put the theological understanding of the Redemption of Christ in its Orthodox context, the compassionate love of God for humanity shown throughout Christ’s whole life, culminating in Gethsemane and then, above all, in the supreme sacrifice of the Cross. Indeed, it is compassionate love which was the leitmotif of the whole of the Metropolitan’s life and work.

As Metropolitan Antony’s brilliant Serbian disciple and another contemporary Church Father, St Justin of Chelije (+1979), wrote: ‘Metropolitan Antony is an exceptional Patristic phenomenon in our times. With his whole being he grew out of the Holy Fathers…he could not speak of them without being moved to tears. In recent times nobody has exercised such a powerful influence on Orthodox thought…He transferred Orthodox thought from the scholastic and rationalistic path to the path of grace and asceticism…tirelessly exercising himself in Patristic feats. In his nature Metropolitan Antony put into practice Gospel love, meekness, humility and mercy. In this the Blessed Metropolitan is an irreplaceable teacher and leader.

There is no doubt in our minds that, as the Local Orthodox Churches, especially the Russian Church, free themselves from the old-fashioned secular attitudes of the decadent twentieth century, the day will come when Metropolitan Antony will be called a saint. Not only all through the Russian Church, but also all through the Universal Orthodox Church. His relics will be taken from Belgrade to Russia in triumph and he will be venerated throughout Russia and the whole Orthodox world. His works will be studied in Theological Academies and seminaries. His life and deeds will be examined and set forth as ‘a rule of faith and model of meekness’. The slanders and persecution suffered by Metropolitan Antony gave him no reward in this life, but we believe that the time is coming when we shall begin to glimpse the reward he has received for them in heaven.

Rejoice, and be exceeding glad: for great is your reward in heaven: for so persecuted they the prophets which were before you.

(Matt. 5,12)

Priest Andrew Phillips,

England

19 June/2 July 2005

St John of Shanghai and San Francisco