FOREWORD

First of all I would like to thank those who invited me here to speak this evening, in particular Burjor Avari. It is nearly seven years since I was last here in Manchester and it is a pleasure to see old friends and acquaintances. Indeed it was due to these friendships that I came to choose this evening’s theme.

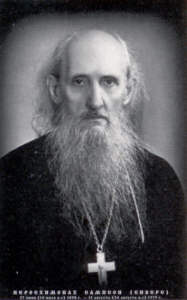

On the one hand, I know Archbishop Anatoliy of the Manchester Russian church, on the other hand, I also know the English church of Fr Gregory and his parishioners. What theme could I take which would be of interest to both groups? Why not the contemporary Anglo-Russian spiritual figure, Fr Sampson, photographs of whom you can see behind me? Moreover, this summer will see the twenty-fifth anniversary of his departure from this world, an anniversary not to be overlooked.

This evening’s talk is based on the five volumes of the biography, writings and photographs of Fr Sampson. It will be divided into three sections with an afterword. Firstly, I will give a lengthy but necessary historical introduction, which will explain something of the meaning of the words ‘Elder’ and ‘Eldership’ in the context of Orthodox Christian society. Secondly, I will give you a biography of Fr Sampson. Thirdly, I would like to give you some of Fr Sampson’s words which I have translated for you and I will comment on their significance in order to bring out his basic teachings.

1) ELDERSHIP

In order to understand the function of Eldership in Orthodox societies, we first have to understand the function of the Church in Orthodox theology. It is expressed beneath the photograph of Elder Sampson behind me, in his words: ‘Learn to walk in the presence of God’. These words sum up the sense of holiness, the sense of the sacred, which is of the essence of Orthodox Christianity. This has again been encapsulated in recent times by St Nicholas of Zhicha, the great Serbian theologian, canonized in Serbia only last year. Writing some sixty years ago in his essay, ‘The Mystery of the Touch’, he said, speaking of twentieth-century Western materialistic values:

"Peace and plenty" - this may be the watchword of secular authorities, but not of Christian clergy. For without holiness God will give us neither peace nor plenty. We mean: the holiness of personal life.

"Organization, organization!" Many shout nowadays. Yes, organization is a good thing, but the holy organization, which is the Church of God, is much better. Any organization without the holiness of personal life, will be like Nebuchadnezzar’s image of metal and clay, broken to pieces by the Rock, Which is Christ.

Elsewhere St Nicholas also wrote:

‘A faith without miracles is no more than a philosophical system; and a Church without miracles is no more than a welfare organization like the Red Cross’.

Another recent Orthodox saint, St John the Wonderworker, of whom many miracles are recorded in all the cities in which he served as diocesan bishop, from Shanghai in the 1930s and 1940s, to London and Paris in the 1950s, and to San Francisco in the 1960s, wrote the following:

‘Holiness is not simply righteousness, for which the righteous merit the enjoyment of blessedness in the Kingdom of God, but rather such a height of righteousness that men are filled with the grace of God to the extent that it flows from them upon those who associate with them. Great is their blessedness; it proceeds from personal experience of the Glory of God. Being filled also with love for men. Which proceeds from the love of God, they are responsive to men’s needs, and upon their supplication they appear also as intercessors and defenders for them before God’.

From the above quotations, both from saints who reposed within the last fifty years, I hope we can see that for them, as for all the Orthodox Christian Tradition, the aim of our lives here is the attempt to attain some measure of holiness, overcoming the faults and failings of our fallen human nature. The same understanding of the Church Fathers, ancient and modern, is of course expressed in all the Gospels and the Epistles, for example when the Apostle Peter writes in 2 Peter 1, 4 that, ‘We are given to exceeding great and precious promises...that ye might become partakers of the divine nature’. Holiness then is the key word to understand our role in the life of the One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church.

Many early Orthodox Christians, as we can read in the Acts of the Apostles and the Epistles, were so close to God, that people tried to touch them or even walk in their shadows (Acts 5,15), convinced that even such slight contact with people of God would be enough to bring them healing. Men and women did indeed seek ‘to walk in the presence of holiness’. After the age of the Apostles, there came Apostolic men, spiritual grandchildren of the apostles, like St Ignatius of Antioch or St Irenaeus of Lyons. Often such charismatic individuals were bishops.

However, by the fourth century, this had begun to change. With the Constantinian settlement in the early fourth century and less and less persecution, those who sought holiness fled to the deserts of Palestine, Syria and Egypt, and then those of Gaul and Ireland. The foundation of monasticism answered the spiritual needs of Orthodox Christians for centuries. People turned not so much to bishops or even priests, who in some cases had become mere administrators or functionaries of an Institutional Religion, but towards monks.

Nevertheless, towards later centuries another particular form of monasticism developed very quickly, this was the spiritual feat of the fool for Christ (1 Cor 3,18-19). This again came as a result of the fact that certain monasteries had become more landholders than spiritual powerhouses. With the turn of the millennium, all these forms of holiness existed side by side. It is not to say that they had not existed from the beginning, it was just that one form of holiness developed more than another, given the specific historic conditions. It was at this point that another form of holiness also came to figure more prominently in Orthodox society. Under the leadership of St Simeon the New Theologian we began to see the more widespread practice of spiritual Eldership, a practice which has been strong in all Orthodox countries from the beginning and ever since. This was no strange development, after all the very New Testament word ‘presbyter’ means elder.

An Elder (in Greek ‘Geronda’ and in Slavic languages and Romanian ‘Starets’) is often, but by no means always, a monk. Sometimes it may be a nun, an ‘Eldress’ or ‘Gerondissa’ or ‘Staritsa’. Sometimes an Elder may be a married priest or a bishop. Elders who are monks may be a priest or may not. However, he is one who is able to give perceptive and clairvoyant advice to people living in the world. This advice is based on revelations and even prophetic foreknowledge, disclosed only to the Elder because he has attained spiritual purity. As the Beatitudes say: ‘Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God’. Purity of heart is thus essential to be truly clairvoyant. This is indeed how we distinguish between the charlatan and the true Elder. ‘By their fruit ye shall know them’.

Whatever the country concerned, whatever the conditions, persecution or no persecution, Eldership has flourished in Orthodox societies. Indeed it can be said that the situation of Eldership is a spiritual barometer which tells you how healthy or unhealthy any given Orthodox society is. In recent years we have seen remarkable Elders all over the Orthodox world, like Fr Cleopa, Fr Paisy (Olaru), Fr Justin (Parvu) and Fr Arsenie (Boca) in Romania, Fr Paisios, Fr Amphilochios, Fr Philotheos and Fr Parthenios in Greece, and a host of Elders in different parts of contemporary Russia. It is to this stream of living spirituality that Fr Sampson belongs.

2) FATHER SAMPSON

A generation and more ago there were many Orthodox who quietly venerated the New Martyrs and Confessors of Russia. Although they had not yet been canonized even outside Russia, let alone by the Church inside Russia, the pious revered their memories, collected details of their lives and miracles, asked for icons of them to be painted, tried to find out where their relics might be, and asked for their prayers, awaiting the day of their formal glorification.

Today in conditions of outward freedom both inside and outside Russia, we are discovering that the list of New Martyrs and Confessors is growing ever longer. Among almost contemporary Confessors inside Russia there stand out a number of Elders like St Kuksha of Pochaev, Fr Seraphim of Belgorod, Fr Tavrion of Riga and Fr Sampson. The latter is of particular interest to the English-speaking world, not only because of his life, but also on account of his origins.

He was the son of Esper Alexander Sievers, a Russian of Danish descent, his mother was English who was to bring up her son as an Anglican. Indeed, his mother, Anne, had been a belle of London society at the end of the nineteenth century, where she had been engaged to an Indian prince. However on the very eve of her wedding, she had discovered that the prince had betrayed her and she had left for Russia and later was to marry there.

The future Fr Sampson was born in St Petersburg on 27 June/10 July 1900 and baptized Edward in the Anglican Church. Brought up as an Anglican by his devout mother, who had been close to Farrar, he was highly educated and spoke six languages. In his teens, finding himself in a spiritual desert, he decided to ask to be received into the Orthodox Church. This duly took place when he was nineteen years old in 1918, when he was received into the Church at Peterhof. The future Fr Sampson quickly initiated himself into the Faith and left neophyte psychology behind him almost at once. Adopting the spirit of Orthodox Christianity, with its spontaneous Orthodox reactions and the authentic practical spirituality of the Church, he was no longer a convert, but an Orthodox Christian.

A year after his chrismation into the Church, he became a novice and there began a life as a monk, hierodeacon in 1923 and then later from 1935 as a priest-monk. This life was frequently interspersed with persecution. In 1929 he had a vision of St Seraphim of Sarov, was arrested again and spent altogether nearly twenty years in concentration camps. Meanwhile, his sister Olga had gone to live in London in 1922, his brother had died of typhus in the early 1920s and his father had died in 1926. His mother became Orthodox through her son and in fact became his spiritual daughter. She died in 1942.

Torture, illness, hunger and sorrow strengthened Fr Sampson, who had a special attachment to the Mother of God, St Nicholas the Wonderworker and St Seraphim of Sarov. In 1946 he escaped from prison-camp, walking 7,000 miles across Siberia. The rest of his life and his role as a spiritual father to a countless number of people, was a story of repentance for his falls. Always penitent for his weaknesses, fortified by the beloved Jesus prayer, in 1967 he received the great schema in monasticism. He reposed in 1979.

Today Fr Sampson leaves spiritual children in Russia. Since his repose twenty-five years ago on 11/24 August 1979, his tomb at the Nikolo-Arkhangelskoie cemetery in Moscow has become a shrine and many have been healed there, even those with terminal illnesses. Fr Sampson helps and strengthens all in the Orthodox Faith and comforts those with family, financial and other difficulties.

In 1996 we had the joy of obtaining the 1,700 pages of the 4 volumes of the Life of Fr Sampson (‘Talks and Teachings of Hieroschemamonk Sampson’). Then in 2002 through the kindness of an old spiritual friend and spiritual child of Fr Sampson, Mother Sergia of the Convent of St John in St Petersburg, we acquired another smaller volume, entitled ‘Your Abba and Spiritual Father Hieroschemamonk Sampson’. Like the previous four volumes this was also published by the Derzhava Press in Moscow and contains reminiscences and many photographs. If you wish, I will pass this last volume around now, so that you can get more idea of him.

3) TEACHINGS OF THE ELDER

a) Humility

The first thing that strikes you about the spirituality of Fr Sampson is his emphasis on humility. Like a contemporary Eldress, the Greek Mother Gabriela, who spent so much of her life in India, or the Russian monk Fr Sophrony, Fr Sampson well understood the secondary place of academic thought. In her aphorisms Mother Gabriela wrote that, ‘No-one has ever seen a saint leaving a lecture-room or a library’, and, ‘Congresses do not solve problems and they are for people who do not know how to solve problems’. As regards Fr Sophrony, we know that as a young man he fled the unedifying academic philosophy of the St Sergius Institute in Paris for the Holy Mountain and for the first time learnt about holiness from the illiterate Russian peasant, St Silvanus. So too, Fr Sampson wrote that:

Knowledge and the knowledge of God are two different things (Y.A., P. 46)

Here he was referring to that knowledge of the world, which we call science (the Latin word for knowledge) and the knowledge of the grace of God, which can only come to us through experience and can never be learnt by booklore. Fr Sampson also said that:

Humility is the source of wisdom (Y. A., P. 48)

These words are particularly important for us. Here this evening, near the Manchester Business School, we may pause to think of the words of the business guru, Peter Drucker, who a generation ago was the first to speak of modern society as a ‘knowledge-based society’ and of workers as ‘knowledge workers’. Without wishing to deny the importance of outward or technological knowledge, Fr Sampson also says that our vocation is to be primarily a ‘humility-based society’ and therefore a ‘wisdom-based society’, and to be ‘humility workers’ or ‘wisdom workers’. Fr Sampson continues:

Humility does not know of submission to demons. (Y.A., P. 143)

Our triumph is humility (Vol 1, P. 300)

Where there is no humility, there is no salvation (Vol 3, Part 1, P. 259)

In this of course the teachings of Fr Sampson are rooted in the Scriptures and the Fathers. He makes it clear that pride is not only the enemy of humility, but therefore the enemy of humanity, when he writes:

All madness is from pride (Y.A., P. 122)

b) Prayer

As regards the question as to how we can obtain humility, Fr Sampson’s answer is also equally clear:

The most difficult thing for us is to acquire humility within us. In other words, never to say anything bad about anyone. (Vol 2, P. 249)

How do we learn never to say anything bad about anyone? He answers us:

Learn, learn, learn to pray the Jesus Prayer - walking, resting (lying down, alone). On your way to work, from work, in the fields, when you go for a walk when you go to the market, when you go to church or seek solitude. (YA, P.60)

In other words, prayer is no some slot in the mornings and the evenings, it is a permanent state of heart and mind. The Elder defines prayer as:

Prayer is conversation with God, it is our mirror. (Y.A., P. 75)

Prayer is the salt of the day (Vol 1, P.98)

Only prayer is the basis of happiness and conscience (Vol 3, Part 1, P. 148)

c) A Christian Life

Fr Sampson comments on the obstacles to prayer. If we are not leading a Christian life, then we shall achieve neither prayerfulness, nor humility, which is necessary if we are to become ‘pure in heart’ and thus see the glory of God and His Kingdom.

We all want to be Christians, but we do not want to carry out the law of love (Y.A., P.34)

As regards our attitude to our secular work, this is also defined in Biblical terms, and not modern Western terms, by him. Since work was the curse imposed on Adam after his fall from grace, secular work can in no way be an end in itself. The result of making it a be-all and end-all is in fact to place on ourselves the curse of spiritual dryness:

Understand that to live for your job is to dry yourself out - to dry up spiritually, to die slowly. (Y.A., P.61)

Certainly we need activity, as it is said, the devil makes work for idle minds, but that activity must not be purely secular. Again, one of the results of secular work can be an activity which is to our spiritual advantage:

Remember that money is like fertilizer for your heart, prayer without alms is like a dry, unwatered tree (Y.A., P.68)

The aim of our life is simple:

Simply love Christ, love Him with all your conscience, heart mind and will. He alone is the sense and aim and joy of life. (Y.A., P. 123)

Always fear making others bitter (Vol 3, Part 2, P. 319)

d) The Future

Finally, I would like to mention two other aspects of Fr Sampson's clairvoyance, his universality and his prophecy, which may have an influence on future generations’ views of him.

Let us recall that he reposed at a time when the Soviet Superpower was ruled by Brezhnev and was about to invade Afghanistan. From visits to Orthodox Russia in the 1970s, I know how the situation stood. The feeling of frustration and blockage made it seem as though the Church would never be free there. And yet he made the following prophecy, a few years before the end:

There remains only a little time to live. Do not waste time on futilities, make haste to live for God - Russia will become small, as in the times of Ivan the Terrible and the border will be along the Pechora. (Y.A., P. 108)

This prophecy was made shortly before he died. Today’s Russian border with the Baltic States and Belarus is in fact near the River Pechora.

Remembering his international background and the six languages which he spoke fluently, there is another prophetic aspect to him which should not be overlooked. With the spread of Orthodoxy around the world, it seems clear that the teachings and prayers of such an international figure may become known worldwide. As he wrote:

Of course my main and fundamental mission is that everyone, everyone might be saved and dwell in joy (Vol 3, Part 2, P.26)

AFTERWORD

Here we are now a few days after the Feast of Pentecost, the Descent of the Holy Spirit on the disciples, and it seems very appropriate that we should now be speaking of Fr Sampson.

I began this talk with quotations from the words of St Nicholas of Zhicha in ‘The Mystery of the Touch’. I would like to end with a quotation from the same source, which I believe illustrates in some way the significance Fr Sampson for us. These words were spoken in the United States in about 1950 at a time when in Communist countries there was a massive persecution against the Orthodox Churches and there were thousands of New Martyrs:

‘Let us not for a moment lose sight of the two ways of reaching holiness in our days. While our brother-priests in the old countries are acquiring holiness through martyrdom, we in the free world are called to acquire holiness through ‘preserving ourselves blameless’ before the Face of the Lord, in body, soul and spirit (I Thess. 5,23). Otherwise we shall not see the glory of God’.

Today, in a political sense, we all live in the so-called free world, therefore these words are very apposite for us all. Fr Sampson did not himself suffer martyrdom, although he came close to it. His earthly life was preserved for us, not as a model of martyrdom, but as a model of confessordom. Today, when we are no longer called to martyrdom, its seems to me that his way of repentance, his virtuous circle, of coming to see God through attaining purity of heart via humility, humility via prayer, and prayer via an exemplary life, is the only way for all Orthodox Christians to follow.

Fr Andrew Phillips,

Manchester Metropolitan University,

3 June 2004